2019 marks the 105th anniversary since the start of the First World War, in which the Abkhaz warriors fought, showing exceptional courage in battle, sincere devotion to the Motherland.

Arifa Kapba

June 28, 1914 in the city of Sarajevo, the Bosnian Serb Gavrila Princip killed the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which led to the beginning of one of the most large-scale armed conflicts in the history of mankind, later called the First World War. The main opponents in it were, on the one hand, the Russian Empire, the British Empire and the French Republic, which were united in an alliance called the Entente - and, on the other hand, the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman empires and the Bulgarian kingdom. The war was officially declared on July 28, 1914. This year marks 105 years since its inception.

Courage and “guilt”

Many representatives of the Caucasian peoples fought valiantly in the First World War under the flags of the Russian Empire: Ossetians, Chechens, Karachays, Circassians, Ingushs, Dagestanis, Abkhaz, Abaza and many others. They proved themselves as brave and skillful warriors, the glory of their military exploits went far beyond the borders of the Russian Empire. At the same time, it is surprising that the mountaineers, in particular the Abkhaz, decided in general to fight this war and voluntarily went to it. After all, the position they had at that time was the most unenviable.

Here is what Caucasian history historian Ruslan Gozhba tells about the time preceding the First World War: “After the end of the Caucasian War (in 1864 - ed.) and subsequent uprisings of the Abkhaz people against the autocracy in 1866 and 1877, Abkhazia was completely empty, 19 thousand Abkhaz remained, then about 10 thousand returned within 10 years. The Abkhaz people were declared “guilty” (the Tsarist government accused them of organizing uprisings - ed.), the population was forbidden to live from the Aapsta river to the Kodor river. Practically, the Abkhaz remained to live here as on a reservation in the Kodor, Samurzakan and Gudauta sections. This “guiltiness” lasted until 1907.”

Even after the removal of the “guiltiness”, the Abkhaz were not taken to the army, except for the Samurzakansk station and representatives of aristocratic families who could still serve.

Defending the Motherland, not as “evil stepmother,” but as “own mother”

When the war began and the Caucasian cavalry division began to form, the Abkhaz asked the royal authorities to include them in the division as a mountain people as volunteers. So the famous Abkhaz Hundred appeared.

“The majority of the riders of the glorious Wild Division (unofficial name, which was assigned to the Caucasian Horse Division - ed.) were the grandsons or sons of former enemies of Russia. They went to the war for their own free will, being forced by no one and nothing. In the history of the Wild Division there is not a single case of even a single desertion,” wrote one of the officers of the Kabardian regiment Arsenyev in his memoirs.

Another eyewitness and a participant in the events of the war, Count Paletsky, who highly appreciated the courage and nobility of the Caucasian soldiers, wrote wonderful lines about the Caucasian division.

It is impossible not to bring this assessment entirely. “The combat successes of the division are enormous. In May 1916, only one Kabardian regiment took Chernovtsy 1,483 prisoners, including 23 officers, and in general the entire division accounted for the number of prisoners four times as large as its composition. The division suffered a lot of losses during its combat activities, but the Caucasian highlanders held and still hold on with great courage and unshakable hardness. This is one of the most reliable military units, the pride of the Russian army. Caucasians had full moral grounds for not taking any part in the war. We have taken everything away from Caucasians: their beautiful mountains, their wild nature, the inexhaustible riches of this blessed side. And when the war broke out, the Caucasians voluntarily went to the defense of Russia, defending it selflessly, not as an evil stepmother, but as their own mother. All Caucasians are as follows: they still live in the true spirit of chivalry, and they are not capable of treachery, and backhands, from the corner. The wars of the Wild Division are not against Russia and Russian freedom, they are fighting along with the Russian army, and ahead of all and daring of all die for our freedom,” writes Paletsky.

When in 1917, General Kornilov was appointed commander of the troops, he announced a review of the Caucasian division, which was considered one of the most reliable units of the Tsarist army. “According to eyewitnesses of those events, Chechens and Abkhaz in white hoods particularly stood out in the divisions. Kornilov, they say, having examined almost 2,000 horsemen, said then: at last I breathed in the military air, meaning “at last I saw the soldiers,” says Gozhba.

“Hundred Crusaders”

The Abkhaz Hundred was part of the Circassian Equestrian Regiment, which, in turn, was part of a large Caucasian Equestrian Division (also included in the division were the Kabardian, Dagestan, Tatar, Chechen, Ingush horse regiments and the Ossetian foot brigade - ed.). Abkhaz fighters were distinguished by exceptional behavior, courage, even among Caucasians. In the “Abkhaz Hundred” there was not a single person who would not be awarded with a combat reward, they were called “hundred of crusaders,” Ruslan Gozhba notes.

The word “hundred” is rather conditional, the historian believes: in total, up to 500 Abkhaz took part in the war. The Abkhaz warriors went to war through mountain passes, through Tuapse, underwent training courses for fighters in Armavir and then just joined the active army.

Ten Abkhaz were awarded the highest military honors of the Russian Empire. According to Gozhba, the name of the commander of the “Abkhaz Hundred” of the Circassian regiment Kornet Konstantin (Kotsii) Lakerbay (Lakrba) was among the twelve best soldiers of the Tsarist army. This list was published in the journal Niva in 1916.

The cavaliers of the Golden Georgievsk weapon “For bravery” from among the Abkhaz were: Ensign Magomed Agrba, commander of the Ingush regiment Colonel Georgy Marchul, lieutenant Varlam Shengelai. The Knights of St. George became: a contractor of the Kabardian regiment Adamyr Tsushba, a soldier of the Abkhaz hundred, Dmitry Achba and Vasily Magba, Konstantin Kogonia, Ramazan Shkhalasov. Abkhaz officers, among them the Ensign of the Tatar Equestrian Regiment, Prince Haitbey Chachba, were also awarded the soldiers' cross of St. George for their personal courage.

Glorious stories

There are many stories of military exploits of representatives of the Abkhaz Hundred. This is, first of all, the feat of the commander of the “wild” division of Cornet Lakerbay himself, but not only.

Among the glorious names of the brave Caucasians is the name of the Abkhaz warrior Georgy Marchula. He was the commander of the Ingush regiment and was considered the best rider in Russia.

“In 1909, these competitions were held in Europe, where the best rider was chosen,” Ruslan Gozhba notes, “then the British and French were considered the best, and he (Georgy Marchul — ed.) led a team of Russian riders at these competitions. They won these competitions, and he was recognized as the god of riding.”

The Ingush respected Abkhaz Georgy Marchul, who led their regiment, called him “Pasha” (the Ingush were mostly Muslims, and the title “Pasha” was a high title in the political system of Muslim countries, originally used for military leaders - ed.) and they even attacked with a song that included such words: “We are not afraid of fear, we are not afraid of bullet, the brave Marchula leads us to attack. We defended with canons, glad from the heart, all of Russia knows, best horsemen are Ingush.” This song is still very well remembered by the Ingush, Gozhba assures.

In the Circassian regiment once was staged a kind of competition to identify the “best warrior.” Many worthy ones were represented, but another Abkhaz, Tarba Akhmadzhira, who was awarded three crosses of St. George, was identified as the best. He also proudly wore a silver watch - a personal gift from the Russian Emperor Nicholas II himself.

And in the next story, Gozhba calls several names of brave dzhigits at once, telling: “When once the warriors were released to rest for two weeks to the rear, they raced, the winner was the Abkhaz warrior Shin Lakoya, who rode before everyone, reared his horse holding it in that position half a meter from the commission, he reported: the rider of the Abkhaz Hundred of Circassian regiment Shin Lakoya. The Circassians, whose horses were considered the best, were a little disappointed with the outcome of the races, and then offered to hold competitions between wrestlers. From the Circassians came out a giant 2.20 cm tall, a representative of the princely Karachai family of Krymshahalovs. Against him, the Abkhaz put forward the valiant warrior Shaman Sabekia from the Abkhaz village of Tkhin. He was tall, broad-shouldered and strong. A few seconds, and the Karachai was on his shoulders, and then again the Abkhaz were stronger.”

11 Abkhaz against hundreds of Austrians

Another hero of the Abkhaz hundred was the glorified Abkhaz Basil (Wasil) Lakoba, who was awarded three George crosses. Together with Cornet Lakerbay, he and several other Abkhaz - there were 11 in total - managed to take the Austrian redoubt.

“The redoubt was on a hill, surrounded by a swamp, and around three rings of wire,” says Ruslan Gozhba, “there were more than a hundred Austrians in that redoubt; after the battle there was a formation of the Caucasian division, which commanded: the Abkhaz - a step forward. The division commander thanked them on behalf of the emperor for taking the redoubt and asked them to name any of their wishes that would be fulfilled immediately after the end of the war. They were told: say what you wish. The officers came forward and said: first of all we want our children, boys and girls, to study, the second is that Abkhazia is not a district (at that time Abkhazia was part of the Russian Empire as the Abkhaz military district - ed.), and the Black Sea province, and the third - the right to bear arms. To this, they all were told that the Sovereign-Emperor asked to embrace each of them and assured that all their wishes would certainly be fulfilled at the end of the war.”

But these desires were not destined to come true. The days of the Sovereign-Emperor were numbered, and the collapse of the Russian Empire itself was not far away.

Memory of heroes creates new heroes

After returning from the fronts of the First World War, many participants in the Abkhaz hundred became active participants in the revolutionary squad of “Kiaraz”, and contributed to the establishment of Soviet power in Abkhazia. Many in 1937 were victims of repression, among them, for example, four brothers by the name of Magba, Wasil Lakoba himself and others.

Today, the names of the participants of the “Abkhaz Hundred” have been undeservedly forgotten, Ruslan Gozhba believes, citing as an example attention to the feat of other soldiers of Caucasians: “It was the centenary of the First World War. In Ingushetia, they erected a monument to the riders of the Caucasian division, at the opening of which they invited the granddaughter of the commander of the Caucasian division, Prince Mikhail Romanov, published an album, they did the same in Ossetia.”

The historian believes that remembering your heroes is the holy duty of every nation. “As philosophers say, honoring heroes brings up and creates new heroes who will always protect their homeland,” he explains.

I would like to wish compatriots, each according to their own strengths, to try to fill this gap, recalling with gratitude the feats of our ancestors, raising children by the example of their courage and nobility.

From the article of Ruslan Gozhba “From the history of the Caucasian Equestrian Horse Division: Abkhaz riders”

10: Horseman Shaman Sabekia

11: Gaguliia Vladimir Dzhgunatovich from the village of Lykhny, 1891

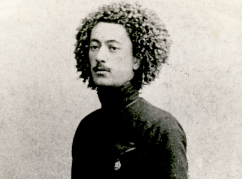

12: Cornet Konstantin Lakerbay with Father Shahan

13: Cornet Konstantin Lakerbay with the nurse and her son (Vozba), Lykhny

14: Cornet Konstantin Lakerbay, 1916

15: Mikha Chirgba

16: Officer of the Abkhaz Hundred Nikolai Aimhaa

17: Abkhaz horsemen: Temraz Lakoba, Wasil Lakoba, Semyon Arnaut, 1914

19, 20: Riders of the Abkhaz Hundred

21: Horseman-officer of the Caucasian division Rauf Agrba, awarded with the Golden St. George weapon “For Bravery”, 1917

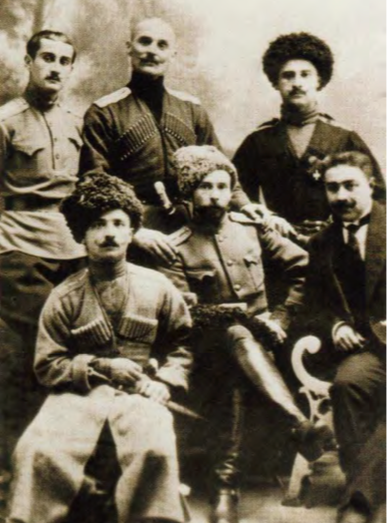

22: Abkhaz nobleman, commander of the Ingush Regiment, Colonel Georgy Merchul (sitting in the center)

23: Constable of the 4th Abkhaz Hundred of the Circassian Equestrian Regiment, full Georgy Cavalier, a native of the village of Achandara, Wasil Magba (Magi)

24: From the right is the full St. George Knight, a native of the village of Kutol Konstantin (Kacha) Kogonia

30: Abkhaz riders before leaving for the front, Sukhum, 1914

18: Riders of the Abkhaz hundred of the Kodor site. In the photo: from left to right sitting: Temraz Kogonia, Shakir, Mitro Akhuba, Nakharbey Gartskia, Kacha Kogonia, standing: Misha Tsaguriya, Kan Katsiya, Nikolay Karchava © From the book by Ezug Gabelia “The Abkhaz horsemen”

25: In the photo: in the center with flowers is one of the founders of the Abkhaz Hundred, Ensign of the Circassian regiment Shakhan Khasanovich Lakrba (father of Cornet Kotsia Lakrba), then the commander of the hundred caps and captain Heinrich Bjorkvist (Finn)

to login or register.