On June 14, the Honored Journalist of Abkhazia, holder of the III Degree Order of Honor and Glory, chairman of the Union of Journalists of Abkhazia, director of the TV channel “Abaza-TV” Ruslan Khashig turns 60 years old. The WAC web information portal prepared an interview with the hero of the day.

Interview by Arifa Kapba

— Ruslan Mkanovich, tell us a little about where you come from, about your childhood.

— I am from the Abkhaz village of Huap. We have a big family: six children, I was the fifth child in the family. Before I entered the school, there was a family council where my uncle Nikolai Chifovich joined (Abkhaz writer Nikolai Khashig - ed.). He very much insisted that I go to study at the Gantiadi boarding school (now the territory of the village Tsandrypsh - ed.). The parents did not agree for a long time, but the uncle was able to convince them, saying: “Is it possible for me to determine the future of at least one of the six children?”

My ancestors in the period of the tragic events of the XIX century (mass forcible eviction of Abkhaz from the territory of Abkhazia - ed.) moved from Pskhu (Alpine village - ed.) to Ldzaa, then Otkhara (Garp), and finally, to Huap at Dbaraa rkhu, where we live now, where our great-grandfather settled. There is our hearth, which fifth generation of the family gathers. My grandfather, father and uncle have kept a special relationship to the house. Now my younger brother Aslan continues the family traditions of our big house, he is the keeper of the hearth.

For example, my uncle lived here in Sukhum, but when he said “going home,” it was about Huap. We have the same attitude.

Every summer, my uncle and I rested in the mountains. In the same place, on the Alpine meadows, he wrote many of his works, periodically he offered to read something, then to describe this or that event in the mountains. Maybe from that time my journalism began. Already from school, I wrote for the children's magazine “Amtsabz”, for the newspaper “Apsny”. The most touching thing is that the staff of these editions, I met them later, answered my letters, and the most joyful thing was to see their publications in the “Amtsabz”. Not to describe the feeling when I received the first fee for my publications.

— Where did you go after graduation?

— It was very difficult to decide on the choice of profession, both humanitarian and technical subjects came easy for me. For some reason I decided to go to the history department, there was a terrible competition at the Sukhum State Pedagogical Institute - 15 people per place - and I did not pass.

As a result, in 1977 I entered the Faculty of Philology and there was also not without a hitch, I almost became a victim of a fight between examiners. The writer Boris Almaskhanovich Gurgulia, who lived with his uncle on the same site, helped. When he saw me with a folder on Prospekt Mira near the building of the institute, he immediately understood that there was something amiss. He returned me to the building of the institute. Even the rector Zurab Vianorovich Anchabadze intervened, and justice was restored - I was given a well-deserved top five instead of the three that had previously been recorded. The most interesting thing is that I later passed the exam four times and each time received an excellent grade at the teacher, with whom this embarrassment arose at admission.

During my studies, I continued working with newspapers. Shamil Khusseinovich Piliya, chairman of the Abkhaz television, who saw my publications, apparently decided that I would be happy to transfer to the journalism department in Tbilisi. All this was connected with the national television that had just opened, with the need to recruit new young personnel. And then one day I, Zurab Argun and Garry Dbar (well-known journalists in Abkhazia - ed.) were invited to his office by the vice-rector of the institute and in a solemn atmosphere read the order that we were enrolled in the Faculty of Journalism at Tbilisi State University. I immediately said that I was not going to go anywhere, although the order for my transfer to Tbilisi had already been signed. They talked to me for a very long time in the party offices, in the city committee of the party. My refusal was perceived as a challenge.

— Why did you refuse?

— I was not ready for this. It was only the second course, I said that I entered here and I want to study for several years, and then we will see. As if I felt what was going to happen.

— Have you already felt the tension?

— Well, in 1979, all this was already, and clearly felt. As a student and living in my uncle's apartment, I read all these letters. For example, I read the famous Abkhaz “letter of 130” (letter from the Abkhaz intelligentsia to the leadership of the Soviet Union about the difficult situation in the country and the need for Abkhazia’s withdrawal from Georgia - ed.) when it was sent to Moscow - when Boris Almaskhanovich and uncle read it, passing each other. As a student, I actively participated in 1978 student protests.

In general, I did not go to Tbilisi, but a year later I had the opportunity to transfer to the journalism department of Moscow State University. Of course, I had quite a few competitors who also wanted to transfer there, but the condition was that the applicant had the skills to cooperate with the media and publications. By that time, I already had many publications. It turns out that backroom disputes have developed around this. I did not know anything - I was at the Olympic Games in Moscow, where, as an excellent student, I received a ticket as a member of the Abkhaz group of tourists. I remember that I came satisfied that I saw Moscow, the Olympic Games - and went further to rest in the mountains, and in Sukhum, it turns out, the question of my transfer was decided. Then they sent a messenger, and within a few days, I traveled to Tbilisi, made the necessary documents at the Ministry of Secondary and Higher Education of Georgia.

With this package of documents, I had to fly to Moscow, but even then, obstacles waited for me. For three days at Sukhumi airport, scheduled flights could not take off due to lack of fuel. The airport was filled with people, and I was among them - without a ticket, with my package of documents that urgently need to be delivered to Moscow. I remember how I showed this package to the airport director Rodion Tarkil, told him about my problem. I was kind of a shy young man and I don’t know where that courage came from, but I told him so: “If you don’t send me to Moscow, I will tear this envelope right here, leave for Huap and not become a student, it depends on you I will become a student of MSU or not”. The airport director imbued and called for the pilot Khariton Gvindzhiya, the flight crew commander to Moscow, and told him: “You have to take this boy to Moscow, it depends on you and me whether he will become a MSU student or not.” And I flew, standing in the cockpit of the TU-134.

— Ruslan Mkanovich, what did the years of study in Moscow give you?

— Moscow is, first of all, the environment. We had 270 students at the course. My group was specialized in working with an information agency, and supervising was by the largest and most important Soviet news agency TASS. In addition to the entire educational process, every week we had one creative day, it was held in the editorial offices of the TASS departments.

Nobody dismissed us during the summer holidays. We were shown a map of the Soviet Union and offered to choose any region for practice. We could go where we want, but not home. My first practice, which I still remember with great pleasure, was held at the editorial office of the “Bryansky Komsomolets” newspaper, where Fazil Iskander once worked.

In Bryansk, I managed to restore the name of one of our compatriot by the name of Gitsba, who was considered to be missing during the Great Patriotic War. He was from Bzyb village. It turned out that he was in the Bryansk forests in the partisan movement, he died there. They were looking for him for a long time in the 70s, they could not find him. I was not indifferent to this topic. While in Moscow, I traveled to the city of Podolsk, looked in the military archives for data on my uncles, my mother’s three brothers. One of them went to the Finnish war, the other to the Great Patriotic War, none of them returned, and I was looking for their tracks. It is because this topic was close to me.

Then in September 1983 my big article was published in the newspaper “Apsny” - a search essay on Gitsba, I submitted it to the faculty on the practice analysis. It aroused great interest, and it was even published in the “Soviet Patriot”, and they presented me with a memorable gift - a ship-sailer with an inscription.

— The first place of work after MSU was the newspaper “Apsny”?

— I got there in 1985 in the translation department. Many now ignore work in print, and this is such a necessary school! In any case, journalism is a pen, it is a paper, now it is a computer, but you still have to write, and even more, since we have bilingualism - Abkhaz, Russian. These five years in the “Apsny” newspaper are definitely not about lost time.

Later I worked in the letters department, in the industry and transport department, which was headed by Huta Dzhopua - a great actor, a great journalist, it was a pleasure to sit with him in the same office. Shalikua Kamkiya was also there, who was the head of the sports department, where I also caught Georgy Janaa, who in my school years answered my letters to the editor. I was received very warmly, at the same time my friend Enver Ardzhenia (now known Abkhaz journalist – ed.) started working at the same time, Daur Inapshba (later known Abkhaz journalist – ed.) came a little later. When the events of 1989 occurred (open confrontations between Abkhaz and Georgians on the streets and squares of Sukhum – ed.), we were young, very active and in every publication gave materials about all the events that took place then.

— Then you came to the television?

— Yes, then we were noticed. And when the chief editor of the Abkhaz television, Vladimir Zantaria, decided to resign, the chairman of the State Committee on Television and Radio Broadcasting, Shamil Husseinovich Pilia, put a condition on him that he would let him go only when he brought the three of us to television. We hesitated for a long time. I wasn’t at all tuned in this way, because I didn’t study television skills, but one day the three of us - Daur Inapshba, Enver Ardzhenia and I - wrote a letter of resignation from the newspaper and switched to television, which was a big blow for our newspaper editor Sergey Kvitsinia. This was in February 1990. Zurab Argun, Garry Dbar, Otar Lakrba already worked there, we joined them. A week later, Vladimir Zantaria went to work at the Writers' Union, and we were left without an editor. Already on April 9, 1990, Shamil Husseinovich Piliya arranged elections of the chief editor of Abkhaz television. So, they chose me.

— And you were the chief editor of the Abkhaz television from that period and during the 1992-1993 Patriotic War, and even longer. How do you rate the work of TV people in that period?

— I am proud that I was at this place on the eve and during the war. We could not have become worthy journalists at that time if there had not been such a friendly team. This includes technical staff headed by Leonid Agrba, Daur Korsaya, Daur Kiut, and in general television is, first of all, a technical base. We, young people of the same age, complemented each other completely. We worked together, waited for the start of the broadcast, and no one left home until the broadcast ended. We have seen that very serious events take place in the society, and the most important thing for us was to be worthy of these events, to adequately cover them, so that people would understand what was happening.

For example, on the first day of the war, which I still remember in detail, our most important task was not to miss something important, to have time to show everything. The television factor played a huge role, because it was the only source of information. Later, when the Eastern Front found itself in difficult conditions, people remembered that there was a radio, and they were looking for radios in every way, and until the end of the war, the radio became the main source of information.

We did not panic, there was no question whether to shoot or not. We continued to work as usually, we simply filmed not the ordinary and political events, but the war. There were few technical possibilities, literally two cameras, but there is a huge creative potential - five film crews at once ready to replace each other. We went on air every day.

We firmly understood what we were doing, and every day we saw the results of our work. But on the other hand, it was a huge responsibility. The specifics of the coverage of hostilities is such a complicated thing that it cannot be learned [theoretically and in advance]. In the same way as our guys became heroes on the battlefield, our journalists, film crews mastered the specifics of filming in a war. Is it possible to take a general plan and at the same time not give out our fighting positions or the coordinates of our military equipment, these are all subtleties ... We didn’t learn this.

We learned this every day, making mistakes, which were also there.

For example, on the day of the terrible tragedy of December 14 (on that day, the Georgians shot down a helicopter at the high-mountainous village of Lata with women and children flying from Tkurchal to Gudauta - ed.) we had to inform what happened, and chasing information we found people who were in the second helicopter that took off from Tkuarchal and then recorded these people on video. Therefore, our hero, whom we interviewed, was in military uniform, although according to the information he was transmitting, there were no militaries in the helicopters, but “only civilians”. Even we had to pay attention to his clothes, and we missed this moment.

The editors of the Abkhaz television was the only organization in Abkhazia that was evacuated according to the laws of war. For three days, we completely evacuated from Sukhum to Gudauta, on the fourth day we created a base there, and all this without interruption in broadcasting. Only one day on August 17th we did not go on the air. However, even this one day without our broadcast for the audience was unbearable, because in the conditions of war they were left without an understanding of what was happening and where.

If we summarize all this, then we can say that our national intelligentsia looked to the very root when they raised the question of creating a national television. If we did not have television, and we would have ended up in 1992 in a war without television, I don’t know how events would turn out, and how our fate would have been.

Today I have anxious feelings for the state of the archive, which we managed to create in such difficult conditions. If we lose at least one shot, we will be guilty before the history, and I consider it very important to digitize the archive and transfer it to the state archive so that it is stored in different places for security purposes. The state and the leadership of the AGTRK need to make a quick decision and finance this work so that not a single shot from the “golden fund” of the military archive is lost.

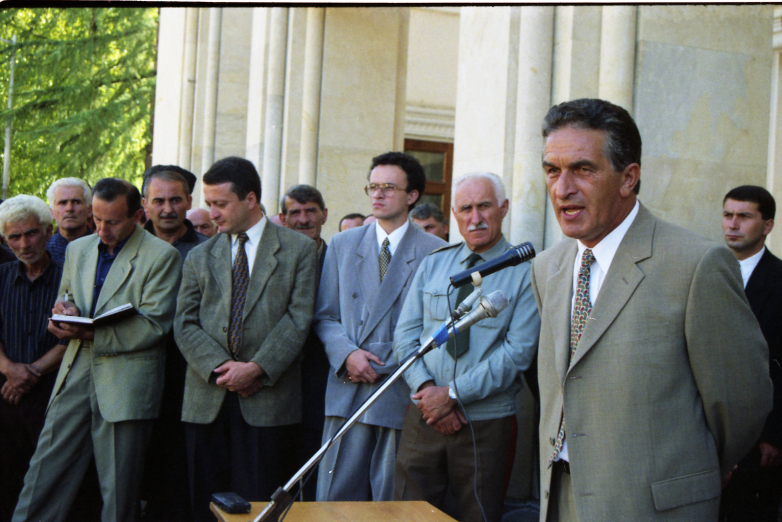

— Ruslan Mkanovich, you, as a journalist, accompanied the first President of Abkhazia on his trip to Tbilisi in August 1997, did a report from the scene. I would like you to tell what was behind the scenes.

— I already did not work on Abkhaz television, I left in 1994 and started creating the correspondent center of the Russian ORT channel (now the Channel One - ed.) in Abkhazia, later became a correspondent for NTV in Abkhazia, and it was then that I was invited to Vladislav Grigorievich Ardzinba. He told me that there is a project [of one] trip, and he wants me to go with him. Frankly, I often had the opportunity to communicate with Vladislav Grigorievich, starting in August 1990, when I first recorded his interview as a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. From that time, during the war and after, on all his significant trips, I accompanied him, including at the famous meeting on September 3, 1992 in Moscow (talks between Vladislav Ardzinba, Boris Yeltsin and Eduard Shevardnadze - ed.).

We had a warm, trusting relationship, and therefore, when he suggested that I once again go with him, I agreed without a doubt, and asked [just] with a small hitch whether we were going to Tbilisi. I have already heard some rumors about this trip, and the person who informed me about this, assured me that it was worth trying to dissuade the President. I have said all this to Ardzinba himself. Vladislav Grigoryevich told in detail that the initiative came from the Russian Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov, and spoke about the route, which was also surprising. Primakov was in Sochi and flew in from the Adler airport on a government plane, sat down at the Gudauta military airfield to pick up the Abkhaz delegation led by Ardzinba. He could have asked Vladislav Grigorievich to come to Adler and from there fly to Tbilisi, but he preferred to make such a respectful gesture.

In Tbilisi, only a limited number of people knew about Ardzinba’s arrival. We flew to the airport. First I and cameraman Mizan Lomia came down the ramp, then the Presidential Guard, and when the Tbilisi journalists saw Primakov and Ardzinba with him, they could not believe what was happening. They waited [only] for Primakov, and therefore they were shocked. While Georgian journalists and I were driving from the airport to the residence of the President of Georgia, they, although they already knew that Ardzinba had flown in, asked me incredulously if it was really him and how this became possible.

First there was the first meeting of the delegations of the parties in the presence of Primakov, then a long conversation between Ardzinba and Shevardnadze one-on-one. When they went to the briefing to the journalists, there was a real crowd of correspondents and operators. Shevardnadze said that the negotiations were delayed and will continue the next day. I remember I was shocked: how is it, why did Ardzinba have to stay there? Neither Vladislav Grigoryevich, nor us [in advance] had any information [about this], everything happened in the course of negotiations.

Returning to those events and asking myself the question, why did he make this trip, I think: did he go there because he had little authority? The image he needed to maintain, the rating was low? No, absolutely! In 1997, all these indicators were at the highest level. I fully realize that Vladislav Grigorievich was very worried about the internal situation in the country - it was the fourth year of the blockade, even in the conditions of war, it was easier. Men could not travel outside of Abkhazia, the economy was in terrible decline and it was very difficult for Abkhaz society to live in such tension. Vladislav Grigorievich was looking for ways, how to “get out”, how to soften the blockade, without giving up political positions. He showed political flexibility, put forward initiatives, agreed to some proposals, hoping that the border regime would also change and the Republic would finally live a real economic life. However, at the same time he never conceded in the main thing and did not cross the red line.

— You are the director of the first in Abkhazia private television channel “Abaza-TV”. How do you assess the development of the channel from the first years of work to this day?

— Without false pathos, I can say that when we went on the air on June 26, 2007, I experienced the same feelings as when I made my first report. Many have tried to prevent us, inspired everyone that it is impossible to create a private TV channel in the conditions of Abkhazia. When I addressed this proposal to businessman Beslan Butba, I did not even personally know him. The only thing he asked me was: is there a potential for creating a whole channel - personnel, creative, technical? For me it was then fundamental to make this channel with Abkhaz personnel, without attracting someone from the outside. The financial opportunities of Beslan Butba and my creative and professional contacts allowed us to invite very experienced, venerable journalists, but we did not. And now we have been on the air every day for almost 12 years, representing an important part of the information field of Abkhazia. If today “Abaza-TV” does not go on the air, it will be an emergency and a phenomenon, people will ask what happened. This is the biggest success for me.

The setting that Shamil Husseinovich Pilya gave me on Abkhaz television back in 1990 is always with me: “broadcast as absolute freedom, broadcast is what I am doing now, without censors from above”. The success of our channel both then and now lies in this. I give this every day to my team and each new employee.

Today, 95 percent of our employees are people who made their first report on the “Abaza-TV” channel. For 12 years, we have changed three teams, but the core remains, and our doors are open. Most of those who came to us were, as they say, “from the street”, without a journalistic education, and now they have a good rating and their own fans. Each of them receives in his work the same level of freedom that I once received from Shamil Husseinovich.

Our communication takes place in the morning at the planning meeting, then the journalists cover the events, write, assemble, broadcast on the air as they saw and understood themselves. I connect only when they call me to help sort out certain nuances and when there are difficulties. When a journalist thinks that after him the manager or editor will look at him, he will continue to be responsible for his material, he will relax.

The journalist must understand that I cannot see the event as he did, because I was not there. That is why I believe that the internal freedom of a journalist is the main achievement of “Abaza-TV”, but it is directly connected with the responsibility of a journalist. If suddenly today the journalist loses a sense of responsibility for what he is doing, tomorrow it is useless for him to appear in the editorial office, this is the authority of our channel. We do not build a broadcasting policy in favor of any political mood - the government or the opposition. Only truth matters.

to login or register.