Much has changed over the centuries in the marriage traditions of the Abkhaz people, but it is also surprising that much has been preserved. On the traditional Abkhaz wedding and how it is celebrated now - in the essay from the ethnographic cycle of the WAC portal.

Abkhaz weddings are famous for their pomp and numerous guests. Has it always been like that? Ethnologists say: not at all. One thing is constant: young people - and today, as in the old days - get to know each other, undergo a pre-wedding period, and, finally, create families.

Armed with materials on ethnography and commentaries of modern scholars, let us recall the ancient wedding traditions and try to find out how they have changed over the millennia of the existence of the Abkhaz ethnos.

Acquaintance

In the traditional Abkhaz society there was almost no premarital courtship institute. The custom did not allow even the young man to speak openly about his feelings, and even more so the girl could not declare her love.

The young man could express his interest to the darling in other ways. For example, to show him crafty, he killed a thrush, put a silver coin in the bird's mouth, "planted" a thrush on a sprig of wild walnut, added fruit to this composition and gave the girl she liked. As a sign of sympathy, the girl, in turn, sent him her handicrafts: a handkerchief, a pouch or a towel. Then the young man could give a larger gift: fabric for a suit or even a horse. In this way, an acquaintance was set up that could end in marriage.

Nowadays, young people do not give each other such gifts. A young man can give a girl a ring as a sign of engagement.

In the old days, like today, the young man could find out the girl’s disposition to him in a following way: he sent a friend to her friend. If it turned out that the feelings were mutual, the official matchmaking began.

The consent of the parties in the matchmaking procedure was achieved by a person with a specially assigned role – ақьаӷьариа ("matchmaker" translated from the Abkhaz - ed.). But matchmaking since ancient times existed in different forms too.

Matchmaking from the cradle

Today, Abkhaz marry according to their own choice: young people can freely meet and communicate at weddings, other celebrations or other public places where they have the opportunity to get to know each other, to understand their sympathies. Nowadays it is extremely rarely that purposefully, for the creation of a family, the elders introduce young people.

In former times, marriages were arranged exclusively by parents: children were not asked about their desire. There have been cases that parents have engaged their children from the cradle: as a sign of engagement, they made cuts on the cradles of both children (this tradition in the Abkhaz language is called агараҿаҟәара - ed); in addition, the father of a boy put a bullet in the cradle of a girl. The bullet served as the key to the fulfillment of the contract. Non-fulfillment of a contract by any of the parties was considered an insult to the second party, and the matter could go to blood feud.

Today this form of matchmaking is lost and is not applied.

In the old days, the Abkhaz were aware of three ways of entering into marriage: open or vowel (argam), secret (mahal) and marriage with abduction (amharsra). All three forms can also be found today, although secret marriages and abductions are extremely rare.

Argama: all parties agree

Most often the marriage in Abkhazia was entered with the approval of the elders in the family. Relatives of the groom came to wed in the house of the bride. The delegation was headed by a respected person in the family name or a neighbor of the groom's parents, who could be their namesake or a representative of another family name. Those who arrived conveyed the intentions of the young man. As a sign of agreement, the side of the bride gave the envoys some kind of personal thing for the girl, that is, there was an interchange of gifts — анапеимдахь еимырдон. This form of marriage is called "argama" - an open marriage, when all parties agree on it.

After such a matchmaking, the girl got married "from her father's house," her husband's relatives came to her, seven or eight people — атацаагацәа.

As we see, in the old days, matchmaking was a whole ritual. The bride's parents were seriously preparing to meet the guests from the bridegroom, and the bridegroom's parents carefully chose who they sent for the bride, who would say on their behalf, "Thank you for trusting us and for having raised the daughter adequately." Today, Abkhaz girls marry "argama", but this, as a rule, is more about a beautiful custom, having lost the old essence.

Abduction and secret marriages

And if the "parties do not agree"? Having received a refusal from the bride's parents, the young man considered himself extremely offended and organized the abduction. It could take place, for example, during national holidays, at the neighbors' wedding, or by prior agreement with the bridesmaids, who cunningly took her out of the house. In short, the groom, intent on abducting his girlfriend, carefully planned everything and waited for the right moment.

The kidnapped girl was not brought directly to the groom's house. She was taken to an influential person in a clan, family name or village. So the young ones sought not only patronage, but also alliances in resolving the conflict. Due to the duty of hospitality, an influential relative tried to settle the case and entered into negotiations with the dissenting party. Usually it ended in peace.

Abduction, as an exception to the rule, can take place today - in the form of taking the girl out of the house by deception. A friend or relative asks to go somewhere or go with her, but instead the boy’s friends take the girl to his relatives. In this case, the future bride may not be aware of the kidnapping.

Another thing is when the girl herself seeks marriage and marries secretly from her parents. The newlyweds temporarily leave the country, and upon arrival they try to resolve the conflict. Here we are dealing with a long-standing form of secret marriage.

In the old days, such a secret wedding (маӡала) was held without relatives and friends of the bride, her parents did not send a dowry, gifts for new relatives. Instead of the bridesmaid there was a young neighbor or sister-in-law.

Eliso Sangulia, a researcher at the Department of Ethnology of the Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies named after Dmitry Gulia, talks about the difficult relationship between a father and his own daughter, which such a marriage could entail.

“There were cases when the father of the bride “gave up” his daughter when she secretly got married, she explains. – he could not communicate with her from a year to five or seven years. But still, especially after the birth of children, they put up and began to communicate. They were reconciled by respected people in the village, neighbors - persuaded the father to forgive the daughter. He could persist, but ultimately forgave. Of course, it happened that the father was dying, never forgiving the daughter without seeing his son-in-law. ”

Dowry, outfits and gifts

Preparations for the wedding began, as now, after matchmaking. The wedding day was appointed, as a rule, by the groom's side. Weddings were usually held in the fall, after the new harvest.

After the wedding date was set, the groom's parents began to thoroughly prepare for it: they poured wine, sowed corn for hominy, and raised poultry. The father of the family grew an animal that was being slaughtered for the wedding and was being prepared as a main dish at the feast. Most often it was a bull weighing 100-120 kilograms.

Weddings were not as crowded as in Abkhazia today, no more than 150-200 people, specifies Eliso Sangulia.

"They invited only the closest relatives, and the wedding was taken over by the neighbors. A few days before the wedding, messengers were sent to villages in the villages, most often the bridegroom and his friend would go around the family and notify about the upcoming wedding. It was not the groom himself who went into the house and called for his wedding; his friend did it. If there was a need, then the relatives helped financially - someone with wine, someone gave a bull. Nobody remained indifferent," the ethnologist notes.

The bride herself was preparing a dowry: not what her parents gave her – аихраҵага, but a different one - hand-made and embroidered pouches, glasses (belts - ed.) and towels. Indeed, after the betrothal, she spent most of her time at handicrafts: sewing, embroidering, and preparing gifts for future relatives. Her friends helped her in this. All this she took with her on her wedding day.

On behalf of the bride, these same hand-made things were "given out" as awards at wedding competitions — for example, to the best horsemen, the masters of the "horse riding art" (аҽҟазара).

There were no wedding dresses as such, or they were not fixed by ethnographic material. The usual dress was sewn from the fabric that the groom brought after the betrothal (аматырбага). The color did not matter, but more often it was white. Usually it was a long "to the toe" and a wide down "Abkhaz dress" with a tight high collar, with long buttoned sleeves (аԥсуа ҵкы). A special feature of the bride's wedding dress was a scarf - "аҭаца касы", which covered her from head to toe.

The well-known ethnographer Elena Malia writes that the scarf was originally white, it was specially knitted from white silk threads, and by the middle of the XX century it was replaced with black chiffon. Today, on the wedding day, the bride does not cover her face, and only during the drive her face is covered with a veil.

The guests presented gifts to the bride, mostly money, and the bride's friend, lifting her handkerchief, showed her face. The bride’s face was usually opened by the groom's parents. Father-in-law usually gave a daughter-in-law a cow, a buffalo or a horse, and a mother-in-law — most often bedding. These gifts became the property of the daughter-in-law.

"Radeda", burning coals and wedding bread

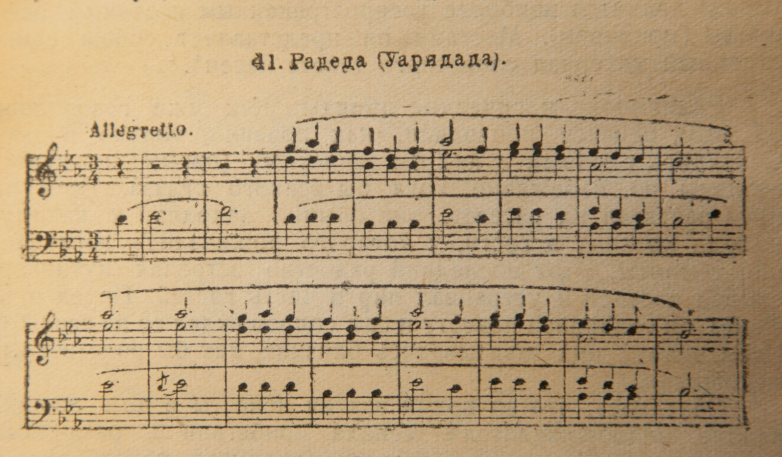

As soon as the bride was taken to the amhara (special house for the newlyweds - ed.) to a special wedding song "Radeda", all the guests were invited to a table under a specially built canopy for the day or two - ашьаԥаԥa.

Men and women were sat separately, young people served. People sat at the table in order of seniority. It should be noted that even today, during the feasts, the Abkhaz adhere to traditional norms of behavior.

On the traditional wedding table they cooked hominy, boiled meat, asydzbal (cherry plum sauce), arashykh (nut sauce), chicken with adzhika, prickly or haricot achapa, cheese, for dessert - akalmish, adzhindzhukh, cooked corn and pumpkin.

If the wedding was celebrated in the winter, in the evenings, so that the guests would not leave the table because of the cold, they would bring burning coals and put them under their feet so that they could warm themselves.

In the old days, the wedding feast lasted two days and was furnished with many rituals associated with the ancient beliefs of the Abkhaz.

For example, the ethnologist Eliso Sangulia told about the forgotten rite of "breaking the wedding bread" over the head of the bride - the Abkhaz people believed that in this way she "became hospitable", and now in her house "bread and salt were enough and there was wealth in everything". This bread or pie (ачашәмгьал) in ancient times was cooked specially. Wedding bread is known to many nations. For example, the ancient Slavs did not hold a single wedding without a loaf.

When the wedding finally ended, all the guests dispersed, and the family fell asleep, only then, under the cover of the darkness of the night, did the groom enter the amhara, and the young were finally left alone in their marriage house.

Another curious touch of the marriage and family life of the Abkhaz, about which scientist Shalva Inal-ipa wrote, should be noted: it was considered unworthy for a man to use his husband’s rights on the very first wedding night.

Amhara, or wilderness

Today nobody builds amharas for a purpose, even the images of these houses were preserved only in old photographs and in descriptions of researchers of marriage traditions.

"Amhara, as a building, is a simple structure, except for its small size, nothing special differs from <...> a hut. It was necessarily built behind the "big house", at a distance of about one to two dozen meters," wrote Inal-ipa.

The construction of the amhara in the old days is the same as now buying an apartment for the young.

When these marriage houses were built, the bride was brought there on the wedding day. The founder of Abkhaz literature and ethnography, Dmitry Gulia, wrote: "Amhara is a house for the newlyweds, literally - inaudible. The purpose of such a construction is to provide the newlyweds from the annoying eavesdropping of various persons, bridesmaids and young people in general."

The origin of the custom of building amhara is not directly related to the regulation of the behavior of newlyweds, although this is perceived by the people in this way. In fact, the very first amharas were built at precisely those times when marriages with bride abduction were widespread: the groom took the girl away "in an unknown direction" and hid in amhara. Here is one more explanation of the name of the house "amkara" – it is translated as "wilderness".

In amhara, the bride remained about two weeks after the wedding, doing needlework and arranging a new home. None of the elders - neither men nor women - entered the amhara. Only young girls could go there. The groom also did not go there in public. This is due to the usual for the Abkhaz modest behavior of the younger in the presence of elders.

Two weeks later, when all the relatives and guests were leaving, a special ceremony was held, which was called “bringing out from amhara” - амҳараҭыгара or “entering into a big house” - аҩнду аҩнагара. Entering into a big house was accompanied by gunfire and a special song.

After being removed from the marriage house, the daughter-in-law became a full member of the family and proceeded to her duties.

Young wife

According to the historian Shalva Inal-ipa, among the most enduring old bans for the bride is a ban associated with conversation and names, which has been preserved in part to our days.

Husband and wife should never, under any circumstances, pronounce the names of each other. Spouses called each other "you" ("уара", "бара"). The husband did not pronounce the names of his wife's parents. A wife should never have called her father-in-law and mother-in-law, and the oldest in her husband's family. She called her mother-in-law "our master" (ҳаҳ), the mother-in-law "our lady" (аҳкәажә). Today brides and grooms call their father-in-law and mother-in-law, as "mother" and "father".

No less strong was the ban on talking to seniors. The bride-in-law never answered the words and questions of her father-in-law, but only silently listened to him, took notes and performed her duties. Such a ban - not to talk with elders - is explained by ethnologists as a show of respect.

Nowadays, as a rule, if the husband’s father wants the sister-in-law to talk to him, then he asks her to talk to him. The traditional Abkhaz families have also survived, where everything is as usual: the daughter-in-law does not talk, does not sit down at the table, does not call her husband and does not name any of the elders by name.

Thus, the preservation of many traditions today largely depends on the particular family, where they are maintained in a more or less traditional form.

Всё очень сложно!

to login or register.