A hundred years ago it was impossible to imagine an Abaza yard without an apiary; beekeeping here has always been an honorable and beloved affair. Today, the situation has not changed much: modern beekeepers only modernized their apiaries, preserving the traditional craft as a real art.

Asta Ardzinba

Beekeeping is one of the traditional agricultural activities of Abaza. For many centuries Abaza people have been famous for their ability to handle bees and get the highest quality honey. Living in the climatic conditions of the mountain forest zone of the North-West Caucasus, Abaza always produced natural, environmentally friendly honey in large amounts.

From the depths of the ages

The valleys and mountain pastures in which Abaza lived were always rich in melliferous plants — wild herbs and fruit trees — which made it possible to collect honey from early spring to late autumn. Almost every family had its own apiary. Honey and wax were exported to Crimea and Turkey or exchanged with neighboring peoples for various goods, whether they were fabrics or morocco.

Medieval researchers and travelers also wrote about the wonderful tastes of Abaza honey. Thus, Baron Fedor Tornau (1810-1890), an officer of the Russian army, writer and famous Caucasus researcher, noted in his memoirs “Memoirs of a Caucasian Officer” that Abaza honey “is very fragrant, white, hard, almost like sand sugar, and is valued very much by Turks.”

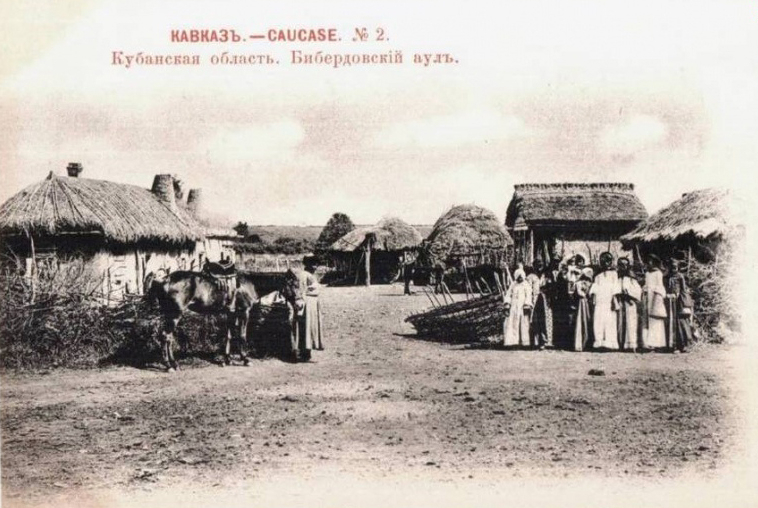

Some sources indicate the number of beehives in a particular Abaza settlement. So, according to the data of 1894, there were 593 hives in the Biberdovsky village, 1320 in Klychevsky, 186 in Kuvinsky, 1114 in Kumsko-Loevsky, 190 in Lovo-Zelenchuksky, 287 in Lovo-Kubansky, and 297 in Shah-Gireyevsky. The fact that such a careful accounting of hives was conducted once again confirms the role of beekeeping as a significant agricultural sector for Abaza.

Honey and wax were among the most important Abaza products that entered the foreign market in the 19th century. In 1812, the Abaza obtained the consent of the Tsarist administration to purchase state salt in exchange for honey and wax at the rate of pounds of honey for four pounds of salt and a pound of wax for 10 pounds of salt.

An even more ancient occupation of Abaza was the collection of honey from wild bees, from which beekeeping later grew. There were rules, the main one of which was: the find belongs to the one who first finds it and leaves his mark.

Pads, baskets and “uyili”

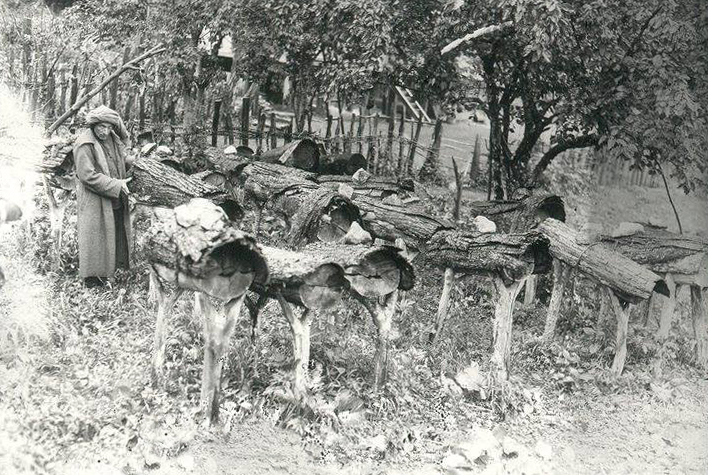

In the initial period of development of beekeeping, bees were kept in blocks, which consisted of two halves of a log with a hollowed core. A small hole was cut out on one of the sides - a bee-entrance, so that the bees could freely fly into these hives. To protect against dampness, the hives were placed on piles, which had the appearance of slingshots. They were protected from the sun's rays and from the rain by the bark, which was removed entirely from broad-leaved trees.

Later, the hives began to weave from hazel in the form of baskets of a cylindrical shape with a conical top. Outside, they were coated with clay. In Russian, such a basket is called “сапетка” (crib), in Abaza - “schamartan” which literally can be translated as “basket with bees.”

Later, the Abaza adopted the breeding of bees from other peoples in wooden boxes - actually the hives, which name in Abaza began to sound like “uyilya”. It is this last method of breeding and keeping bees that has survived to the present day. In the past, honey was not distilled, but stored in a honeycomb, and, when needed, cut off with a knife.

There is matriarchy in the bees’ family and the most important is the queen bee. She is also the main long-liver: sometimes she lives up to three years. During this time, several generations of working bees and drones succeed. The first usually live no more than a month, the latter - up to six months.

There is an ancient custom according to which a swarm that flew away with a bee belongs to the one in whose yard it landed.

With delivery to honey plants

Abaza did not give up beekeeping even in the most difficult periods of their history, including during the forced relocation from the highlands to the foothill-steppe zone during the Caucasian War.

Abaza honey is still highly regarded today. A large number of families in Abaza villages maintain their own apiaries. Except that there is no export to other countries now, and they are not involved in beekeeping on an industrial scale either.

In addition to the traditional apiaries in Karachay-Cherkessia, today you can often find apiaries on wheels - these are long carts with beehives that roam from one flowering field to another.

Experienced Abaza beekeepers say that such an apiary can increase the amount of honey collected several times. The fact is that bees, when placing honey plants several kilometers from the hive, eat some of the nectar on their way home, so the use of mobile apiaries allows you to collect beekeeping products more efficiently. According to experts, the use of this method increases honey collection by about 50 percent compared to the standard method.

With the help of a specially equipped van or car trailer, beehives can be transported directly to honey plants. Thus, bees can collect nectar from one particular plant, for example, acacia, flowering buckwheat or linden, which ultimately affects the quality of the product. Some beekeepers move the apiary several times a season, and this is justified.

As in any other business, the movement of honey insects to rich sources of honey collection (bee, nectar and other medical products - ed.) has its own subtleties. For example, transportation is done after the flowering of the main honey plants. It is also important to find out if there are other apiaries within a radius of two to three kilometers, so as not to create competition. Beekeepers, as a rule, receive permission to place an apiary from the owner of the field. Although this is more a formality: beekeeping at Abaza has never been hindered.

to login or register.