The WAC is reviving the tradition of the Abkhazian ritual candle: for the second year in a row, on the day of remembrance of the victims of the Caucasian War, in May, ashamaka was lit. What is this tradition, what are its roots and history? The Information portal of the Congress has prepared a detailed material about this.

Said Bargandzhia

Modern life, digital technologies, globalization - all this is rapidly replacing centuries-old national traditions, something without which our ancestors could not imagine their existence relatively recently. Yet, some customs, albeit in a distorted form, are still alive. Fortunately, many people in Abkhazia carefully preserve this knowledge, trying to pass it on to new generations. These are scholars and historians, ethnographers who scrupulously record the memories of the elders, and then collect the material into books, which gives hope for the preservation of national wealth. The World Abaza Congress, one of the main goals of which is to preserve the language and traditions, asked experts about one of them and presented valuable information in detail. It will be about the ashamaka candle.

Akialantar, aokum, ashamaka

Funeral and memorial rituals generally stand apart in the traditions of the Abaza people and, in general, the mountain peoples of the Caucasus. From time immemorial, the Abkhazians treated the souls of the dead with special respect and accurately performed all the necessary rituals passed on to them by the older generations. This is still largely the case.

In the funeral rites of the Abkhazians, a special place was given to tree-like candles. There are three types of them: akialantar, aokum and ashamaka. These are ritual candles. They were made from long waxed ropes, which were applied in different ways around the base, forming a three-dimensional figure. All these candles were lit in memory of the deceased, but they were intended for different categories of deceased people.

The akialantar candle was lit exclusively in memory of the deceased man, who did not have time to start a family and did not leave descendants, and he was the last successor of the family. For example, the family had an only son who passed away without leaving descendants, therefore, the clan ended on him. The akialantar candle reached a height of five to six meters. Broom rods were woven into it, gunpowder was poured into the very top into the notch. When lit, the candle "shot", so it was installed either in the courtyard or in the cemetery at the grave of the deceased.

The aokum candle was lit in memory of the deceased of any gender, but only to an unmarried man or an unmarried girl - also without offspring. Aokum was lit if the family had successors. For example, one family had two sons, one had a family and children, another one did not, and the other passed away. However, the heirs still remained - from his brother. The aokum candle was multi-level; it consisted of four parts that were installed on top of each other. Weaving was made in the shape of a cross, with an overlap.

Ashamaka occupies a special place among the memorial candles. We will dwell on it in more detail.

Sacrifice and Ashamaka. Etymology of the word

Ashamaka was lit in memory of the deceased, man or woman, on the anniversary of his passing or on the 40th day from the death of a Christian and on the 52nd day of a Muslim.

Ashamaka could be of different lengths. To make one ashamaka, one and a half to two kilograms of good wax, preferably yellow, were required.

It should be noted that not all types of funeral candles were always made in the house of the deceased and not by his household. Women collected candles, as a rule. It could be a married sister or aunt, who lived separately. If the family did not know how to make a candle, there were always skilled craftsmen nearby who could help with this, but a close relative of the deceased was sure to take part in making the candle.

Director of the Abkhazian Institute for Humanitarian Research named after Dmitry Gulia, a member of the Supreme Council of the WAC Arda Ashuba studied the topic of ritual memorial candles in the traditions of the Abkhazians. He said that earlier, if a woman did not have the opportunity to make ashamaka for the deceased - a close relative - she considered it a shame, an unfulfilled duty of memory of a loved one. If those who knew how to make a candle helped, they never took money for it.

The ashamaka candle was once always brought along with the sacrificial animal. It was a bull if the deceased was a man, and a heifer in case of a woman. It is important to understand that sacrifice was accompanied by many traditional Abkhazian rituals, and funeral rites are no exception.

"No matter how many goats a person had, he sacrificed only a sheep or a bull (heifer). At the same time, the ashamaka was not attached to the lamb. The bull at the commemoration was wrapped in mourning, its horns were wrapped in a candle and brought as a gift to the deceased," says Arda Ashuba.

Translated from the Abkhaz language, "ashamaka" just means "cattle". If close relatives could not bring the sacrificial animal, they brought only a candle, which they later began to call ashamaka. Thus, ashamaka was often equated with a sacrificial animal.

According to the Abkhazian scholar, member of the Supreme Council of the WAC Jambul Injgiya, who also studied this issue, this version is the most real. He voiced two more versions of the origin of the word ashamaka. "Ascha" (in Abkh. ашьа) – means "blood" in Abkhazian, "amaka" (in Abkh. амаҟа) - "belt", and, as we know, only close relatives lit a candle". The latest version is that, according to the Abkhazian tradition, it was possible to sacrifice at least a two years old animal. "Amaka" can also be translated from Abkhazian as "old", hence the word ashamaka itself.

How ashamaka was made

Several interpretations of the manufacture and use of the ashamaka candle have survived to this day. According to Ashuba, the candle should have been enough to burn during the meal. It was believed that if you extinguish it earlier, the spirit of the deceased would be "upset", since he was "rushed", "not allowed eating". During the burning of ashamaka, a woman was present who brought a candle; she unwound waxed bundles, maintaining the fire. According to the expert, the candle did not burn out until the end; the remaining waxed bundles were unwound and handed out to those present at the commemoration.

The tradition of ashamaka was studied in detail by the outstanding Abkhazian scholar Elena Malia. Her research is called "The tree of candles in the memorial rituals of the Abkhazians" and was published in the book "The Caucasus: history, culture, tradition, languages." Malia, in turn, writes that the ashamaka burned from midnight until almost early morning. The remaining waxed tourniquets were distributed exclusively to men; they were used for domestic needs.

In her research, Malia notes that those who came to the commemoration could have brought more than a dozen ashamakas.

There was a special technology for making candles.

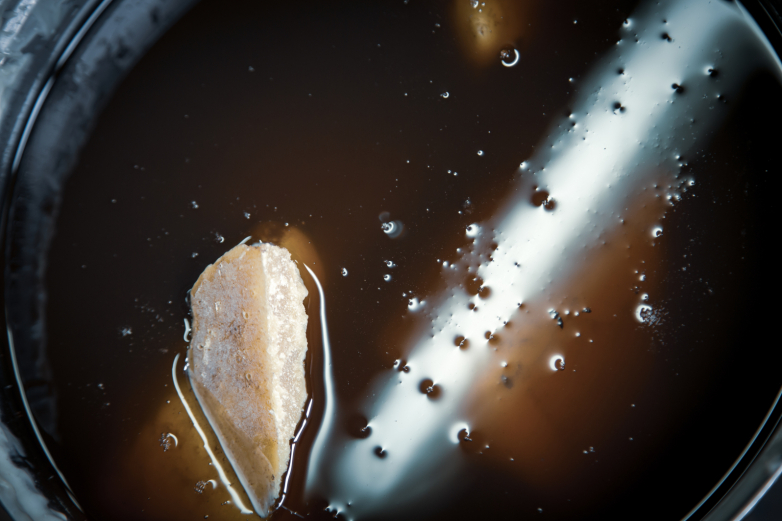

"They melted half of the wax in a cauldron, and immersed the base in a hot solution for two minutes, it was called in Abkhaz ачылара. They pulled out the waxed cords, and then two women, taking the cords by the ends, twisted them in different directions. The third ran a rag over the tourniquet. This made the tourniquet round. To evenly coat the tourniquet with wax, the same operation was performed a second time using the remaining wax," said Malia.

Ashamaka was placed on a stand, which was made separately and made of wood. The wooden stand consisted of three legs and was made by men. At the same time, an elderly "pure" woman had the prerogative of weaving the candle itself, explains Elena Malia.

According to the scholar, special attention was paid to the decoration of the upper part of the ashamaka. Twigs of trees bent into arcs were attached to it, or crossed wires, called "hands" (анапкуа), were attached. Later, ashamaka was decorated with ajinjukh (an Abkhazian dessert - nuts strung on a string and covered with thick porridge made of grape juice - ed.) or sweets.

Commemoration of the deceased

The Abkhazians believed that during the year the soul of the deceased is in the house and does not leave it, moreover, it "dwells" in the clothes of the deceased. There was a tradition to lay out the clothes of the deceased on the bed as if they were worn by someone. This custom follows

precisely from the belief that the soul of the deceased "dwells" in his personal belongings for up to a year. Every day for 40 days after death, if the deceased is a Christian, and 52 days if a Muslim, and then, up to a year, once a week, the family laid the memorial table with food. A chair was put to the table; the front door to the room was ajar. The hostess, going up to the table, lit an ordinary small candle and pushed aside the chair, tried a little bit of each dish. After a while, she put out the candle. It was believed that the soul of the deceased should "get enough food." The Abkhazians thought that if the soul is not satiated, then it can "harm loved ones."

The laying of the funeral table in the family was stopped after the so-called "big" commemoration - a year after the death of the person. They tried to hold them especially magnificently and solemnly. All relatives came to the commemoration, brought specially prepared dishes, fruits, various sweets. Close relatives brought the sacrificial animals and lit the ashamaka. Therefore, according to traditional Abkhazian beliefs, the earthly path of the soul of the deceased ended. The Abkhazians have preserved these memorial traditions to this day, although in full the rite of "great commemoration" can be observed extremely rarely.

Fascinating sight

Nuri Kvarchia, a member of the Supreme Council of the World Abaza Congress, head of the Center for Folk Art of the Republic of Abkhazia, describes very interestingly and vividly such a commemoration - with a sacrificial animal, with the lighting of ashamaka. He saw the rite only once in his life, and then he was no more than 6 years old. He remembered such an unusual action for the rest of his life.

"We lived on the outskirts of Tkuarchal, in a fraternal settlement of the Kvarchia family. Nikolay Kvarchia, who had seven sisters, also lived there on a hill. They were married by that time, and Nikolay had seven sons-in-law. He was a well-respected person. When he died, his family accompanied him on his last journey in a manner due to Abkhazian traditions," says a member of the WAC SC.

Nuri Kvarchia recalls that on the eve of the commemoration he heard from his family that Nikolay's sister would come to honor his brother's memory and bring ashamaka. Together with the other children, the little boy was looking forward to the arrival of the ashamaka. Nuri remembered that the bustle around ashamaka resembled the excitement during the bride’s arrival.

"Suddenly there was a shout in the yard and we saw a group of people approaching the house. It was getting dark, it was difficult to see people in the distance, but I saw the lights, like little stars falling from the sky. Such things seem magical to a child. I ran with other children to meet those who came, I could not wait to take a closer look. The newcomers were in deep mourning and were leading a sacrificial animal - a bull, on whose horns lighted candles were attached. Those walking in front held the ashamaka memorial candle, it was so heavy that it was impossible to lift it alone. Those who arrived entered the courtyard screaming and crying, as is usually done on the day of the funeral, and mourned the deceased at the location of the anschan (the place in the house where the belongings of the deceased are kept until the anniversary - ed.). I remember this tradition with lights and various tints of light from a candle at dusk as something amazing and spectacular. All this fascinated me, now I remember this past time as a dream. Since then, I have never had to witness such a ceremony," recalls Nuri Kvarchia.

Ashamaka and religions

Many Abkhazian ethnographers believe that, despite the constant influence of various cultures, the Abkhazians continued to preserve their traditions, as if "weaving" them into religious customs. The same can be traced through the tradition of lighting the ashamaka. It was a primordial Abkhazian tradition, not associated with any religion. In general, the Abkhazians have always been very respectful of religions; they were distinguished by amazing tolerance. If the neighbor was a Muslim, he was never offered pork, and if a Christian, then during the fast he was not tempted with meat or dairy food. Both those and others raised a toast in the name of the Almighty (a traditional Abkhazian feast begins with a toast to the Almighty - ed.), and if they gathered at the memorial table, they made a toast to the peace of the soul. Today, more and more often, on the day of the funeral, a priest or mufti is called to perform the prayers prescribed by religion.

Ethnographer, member of the Supreme Council of the WAC Marina Bartsyts says that the Abkhazian belief carries elements of syncretism (a combination of heterogeneous philosophical principles in one system without their unification - ed.).

"We celebrate Christian Easter, Muslim fasting (аурычра), even the influence of Zoroastrianism can be traced (the ancient Abkhazian tradition of jumping over the fire - ed.), that is, all the great world religions have influenced the Abkhazian culture. That is why we light a candle on Нанҳәа (August 28, the Orthodox holiday of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos, and in the Abkhazian religion it is the day of remembrance of the dead - ed.) we light a candle, although the believers say it is not necessary. Despite the influence of other religions, Abkhazians still carry their ancient tradition of lighting a candle, which comes from the depths of millennia," Bartsyts said.

Marina Bartsyts recalls that the tradition of lighting candles for the repose of the soul is found in many cultures around the world.

"If we take the peoples of the Caucasus, we can say that the Abkhazians have preserved the most archaic features of this rite. The ashamaka candle symbolizes the union of two worlds - living and dead, "the tree of life". The word "candle" (ацәымза) itself is translated from Abkhaz as "wax pine tree": ацәа - wax, amza - pine. There was a pine tree in the core of the candle, branches were made at the candle, and a bird was placed on top, which, as a rule, was made of wax or pine wood. The bird is a symbol of the sky," said Bartsyts.

She also reminded of the traditional Abkhazian worldview: at birth, each person is determined "his share" of everything - the share of life, happiness, prosperity, wealth, but when a person dies, "his share of his soul" (including food and light) he must "get from the world of the living." Therefore, celebrating the anniversary of the deceased, they light a candle and set the table.

The modern tradition of lighting ashamaka

Arda Ashuba says that today the ashamaka memorial candle is made and used by few, including because of a misunderstanding of its purpose and some difficulties in its manufacture.

Marina Bartsyts says that nowadays the lighting of ashamaka, if it occurs, is often in cases of early death of a person.

The tradition of lighting the ashamaka is revived by the World Abaza Congress, which makes and lights the ashamaka on May 21, the day of remembrance for the victims of the Caucasian War.

The traditional Abkhazian candle for the WAC was made by the famous Abkhazian artist Batal Dzhapua. He says that he tried his best to follow the rules by which the candle was assembled in the old days, and that the process was generally the same.

"The only thing is that it is easier for us, because we can use narrow cotton medical bandages for the base of the candle. We buy them, twist them and then dip them into melted wax. In the old days, this was a more difficult task. Cotton was specially grown - of course, for general needs, but, at the same time, for making candles," says the artist.

The rest of the technology is about the same as centuries ago. The artist also melted the wax and then stretched the bandage prepared for this through the melted wax.

"After the first time, the thread is a little rough, so it needs to be sanded with a cloth. Then, for the second time, dip it into the melted wax in order to get a round cord candle, the same along the entire length and thickness," shared Dzhapua.

At the heart of the candle is a wooden rod on which the entire structure is wound. In some cases, when the candle is large, the rod is made of cardboard paper, which burns along with the candle.

"The number of cords depends on the diameter of the candle base. The larger the diameter, of course, the more there are cords. There is some geometry that you need to know. You need to understand the diameter of the base, divide it into four parts around the circumference, draw vertical lines," the artist said in detail.

Despite the fact that the tradition of lighting the ashamaka, like many others, is gradually becoming outdated, we, the Abaza people, are obliged to keep the memory of them, passing them on to new generations. Customs and traditions were the guiding stars of our ancestors. Perhaps it was precisely following them that allowed our ethnos to survive, to avoid the terrible fate of extinction that befell many peoples of the world.

to login or register.