July 20 would be the 95th anniversary of the outstanding Abkhaz woman, the first woman sculptor, laureate of the Dmitry Gulia State Prize, a member of the national liberation movement of the Abkhaz people in the years of Georgian oppression Marina Eshba.

Said Bargandzhia

Not to miss important details, to show the scale of the hero, to tell about victories and defeats in her life - these are probably the main tasks of the author, who is going to tell about an outstanding personality. And yet - how can they be performed at 100 percent? After all, it is impossible with “surgical” precision to convey all the experiences, fulfilled and unfulfilled dreams of a person, to tell about her thoughts before sleep, about what made her smile or, on the contrary, feel sad ... It is impossible to fit the greatness of the person into words: there is always a feeling of incompleteness and understatement. Such a feeling arises when you try to talk about Marina Eshba, the first Abkhaz woman sculptor. Her life story will forever remain in the history of Abkhazia as the path of a bright and talented person of strong spirit.

Famous family

July 20, 1924 in the family of the prominent Abkhaz revolutionary and fighter for the independence of Abkhazia Efrem Eshba, daughter Marina was born. In those years, Efrem Eshba together with his wife Maria Schigrovskaya lived in London, Eshba worked in the trade mission of Soviet Russia. But soon after the birth of Marina, the family had to leave the country, because of persecution of Soviet representatives in England.

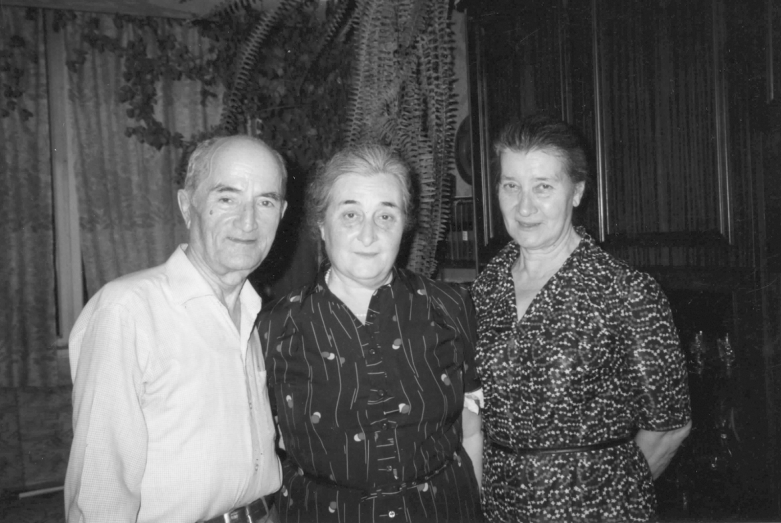

They moved to Moscow. In 1926, another daughter was born - Lisa. The sisters, Marina and Liza, were tied to each other since childhood and carried this bond throughout their lives.

After another 10 years, in 1936, the women of the Eshba family were left without a main defender: Efrem Eshba was sent into exile to Kolyma, and three years later he was shot. Details of the death and burial place of the famous father of Marina became known only about a year ago. Then, three years after Efrem Eshba was sent into exile, he was shot in Lubyanka. He was buried on the territory of the former closed NKVD facility (the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs of the RSFSR — the central government body of the RSFSR for fighting crime and maintaining public order in 1917–1930 and in 1937–1946 - ed.) in the village of Troitsky district near Podmoskovye (now - new Moscow - ed.).

When her father was taken away, Marina was 12 years old. All subsequent years, until she was old, she clung to any thread in order to find out at least something about a dear person, even found his cellmates. Over the years, she began to realize that he was no longer alive, but she never learned all the details.

Marina, Olga and “Olka”

More recently, in June of this year, a book about Marina Eshba “Talent and Femininity: Marina Eshba through the prism of time” was published. The author of the book - art historian Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel - tried to collect the memories of relatives of Marina, and shared her own.

Olga immediately suggested that our interview with her be held at her home, because in this house Marina Eshba was a frequent guest.

“She loved to come here, spent a long time contemplating,” smiles, standing on the balcony of her house, Olga.

This modest house is at the same time a corner of the dream of a house by the sea: a blooming garden, powerful spreading trees, the sound of the sea surf and the sea itself is in two steps, a balcony immersed in greenery - the most famous balcony from distant years of the last century.

It was a special place for Marina Eshba: here with her close friend, Olga's mother, by the way, Olga too - they had heartfelt conversations, shared secrets, and escaped from the summer heat. Well, Olga, the youngest then, at the end of the 60s of the last century, was still “Olka” - so Marina Efremovna, “Aunt Marina” so lovingly called her motherly.

At the time of their first meeting, Olga was five years old. A friend of the mother on the rights of a close family man could give the girl advice or scold for a childish prank, but always “with her customary intelligence.”

“I considered Marina to be practically my second mother, we met almost every day. She was a very strong person. First I was afraid of her: she demanded to do what she wanted, and not otherwise,” recalls Olga.

The idea to write a book about Marina Eshba was presented to her by the famous Abkhaz historian and ethnographer of the Mira Hotelashvili-Inal-ipa.

“Almost immediately after Marina’s death, I met Mira Konstantinovna on the street. We talked to her for a long time, including about the irreplaceable loss for Abkhazia, about the fact that Marina Efremovna was gone. It was then that she began to convince me to write a book, said that no one knew her as closely as it fell to me to know. I will not hide, the words of Mira Konstantinovna have sunk into my soul,” says Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel.

According to her, the task was not easy: to translate the image of a woman of this scale on paper, to remember the life next to her year after year.

“I had no idea where to start. I wrote something, then put it off, reread it again, made changes. Sometimes I was angry, tore the material into pieces, then calmed down, sat down and reassembled everything bit by bit,” says Olga.

This difficult, sometimes painful process eventually brought its fruit not only in the form of a published book, but also in the form of invaluable conclusions for the author himself. Olga writes in the book: collecting, bit by bit, the memories of those who knew Marina Efremovna, she “was once again convinced that people perceived her as a person for whom art and human constituted an indissoluble concept”.

Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel cherishes the memory of Marina. Walking through the house, every now and then remembers the details and such important “little things”. “At this table, we often all sat together ... They loved to spend time in the courtyard, especially in hot weather ... Marina loved to watch the sea ...”, recalls the art historian.

The first Abkhaz woman sculptor

Describing the biography of Marina Eshba in the book, Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel mentions the inclination of the future sculptor to the exact sciences, which influenced the search for the path of the artist in her youth. Since childhood, Marina has shown aptitude for mathematics, and after the end of World War II, she entered the Tbilisi Polytechnic Institute. She studied well, when suddenly ... she decided to leave the polytechnic institute and enter the Moscow Institute of Decorative and Applied Art. So often happens to people who are aware of their true path. So she was the first of the women of Abkhazia who became a sculptor.

In Moscow, Marina learned the basics of sculptural mastery from Yekaterina Belashova, a very famous master.

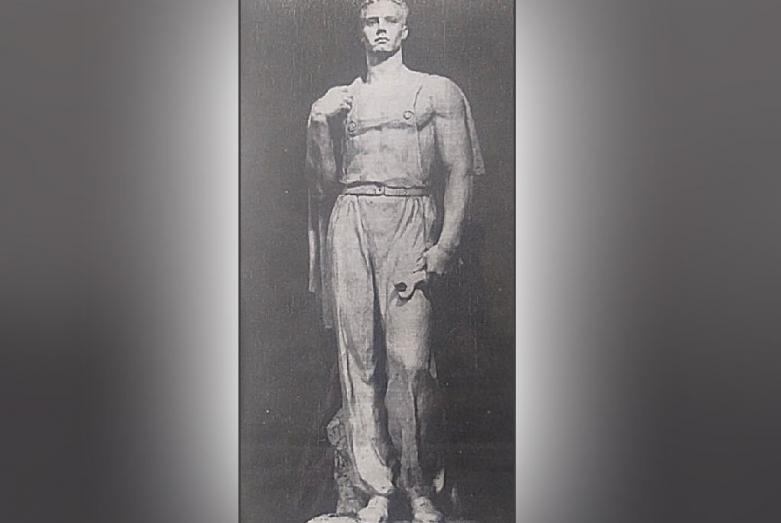

Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel traces in detail the formation of Marina as a sculptor. She writes that Eshba received her first important order, working in the workshop of Georgy Motovilov, where she came in 1953 (Georgy Motovilov, the USSR State Prize winner, is known as the designer of Moscow Metro stations and author of the monument to Alexey Tolstoy in Moscow - ed.).

“The studio was asked to create an image of a worker for installation at the House of Science in the center of Warsaw, the capital of the sister Polish People’s Republic,” Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel wrote about this work.

Portraits of celebrities and a monument to the father

Marina quickly proved herself as a talented and professional sculptor.

She took part in All-Union competitions and won victories. Eshba produced projects of commemorative medals: the 800th anniversary of the founding of Moscow, the 40th anniversary of the death of 26 Baku commissars. She also completed sketches of the medals “50 years to the Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR”, “150 years since the birth of N.А. Nekrasov”.

Her hand belongs to the portrait of the composer Mussorgsky for the Soviet pavilion at the World Exhibition in Brussels in 1957. She also created the images of the great representatives of theatrical art - Stanislavsky, Schepkin, Yermolova, deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Vasily Lakoy, who were highly appreciated by critics and art critics.

In 1961, Marina became an honored art worker of the Georgian SSR. Representatives of the art of Abkhazia received such high rank infrequently. Of course, by that time Marina was already an honored artist of the Abkhaz ASSR.

In the early 1980s, a memorial complex was opened in Gudauta dedicated to the memory of soldiers - residents of Abkhazia who died in the battles of the Great Patriotic War. Marina worked on it in collaboration with architect Tamara Lakrba. Seeing this complex, residents of the village of Lykhny wished to erect a similar memorial in their village and raised money.

Marina again acted as the author of the complex, this time with her friend, the Moscow sculptor Vera Akimushkina.

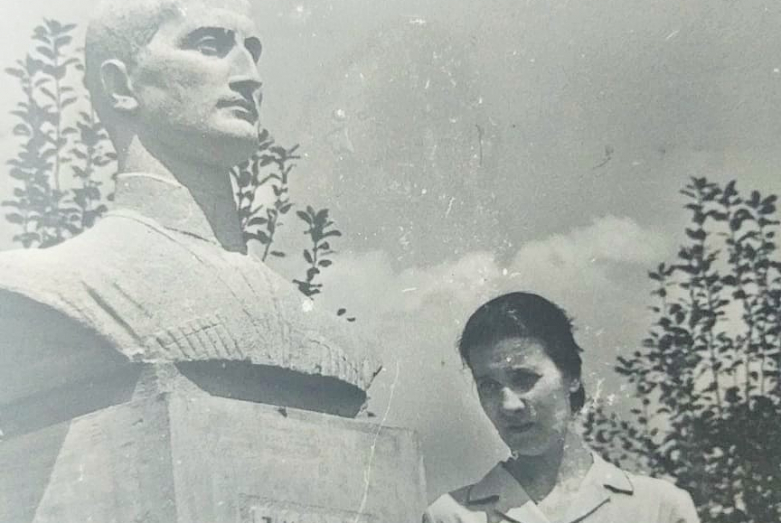

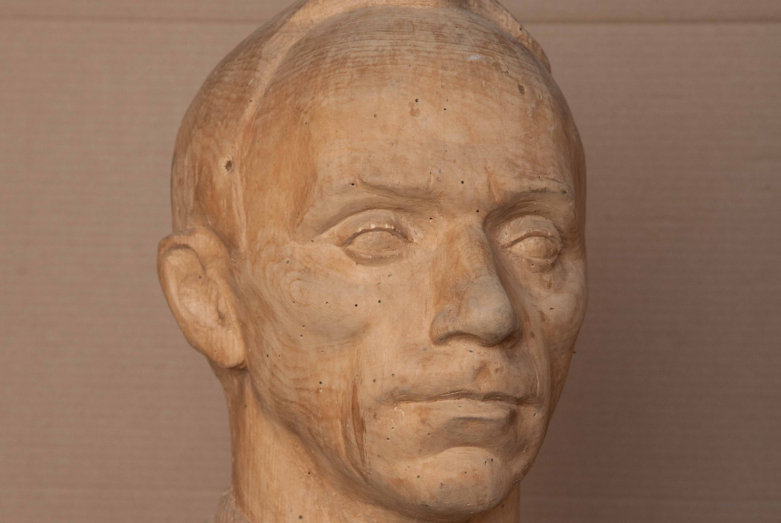

Marina’s career had a lot of loud and bright works, but the main work of life was a monument to her father, Efrem Eshba, in the center of Sukhum.

Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel recalls that on the opening day of the monument, Marina cried for a long time and could not stop herself.

After the Patriotic War of the people of Abkhazia, the monument of Eshba was literally shot. According to Olga, after that Marina intentionally refused to restore him, seeing in this a sign of fate, although she did not know the exact fate of her father.

Return to Motherland

Having settled in Moscow, having many friends and professional contacts there, the sculptor at the same time always sought homeland. Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel explains that Marina Eshba could not imagine herself without Abkhazia, without Ochamchira.

“She meets Tariel Arshba, the leading correspondent of the “Sovetskaya Abkhazia” newspaper. Leaving Moscow and friends, she married Tariel, and in 1960 they had a son, Vladimir,” writes Olga in her book.

The son always remained the main person in the life of Marina. Today, Vladimir lives in Sukhum, but does not like to communicate with journalists, he prefers to remain “in the shadow.”

Marina’s first marriage, however, broke up, and after years, Marina married a second time. Her husband was Nuri Akaba. They lived together for the rest of their lives, until the death of Nuri, whom Marina was very hard on.

Modest person and brave fighter

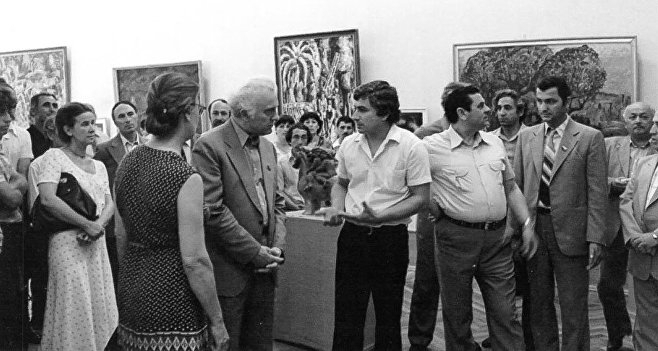

In 1962, Marina Eshba headed the Abkhaz branch of the Union of Artists of the Georgian SSR. Her main goal in this position was to make the organization of artists of Abkhazia autonomous. Her efforts were not in vain: a few years later, Eshba headed the Union of Artists of the Abkhaz SSR. But this was preceded by a long and stubborn struggle, in which Marina showed herself as a brave and fair leader.

Olga Voitsekhovskaya-Brendel writes that the most prominent manifestation of Marina’s activities at the head of the Union of Artists can be considered the organization in 1966 of a group exhibition of Abkhaz artists in Moscow. It should be understood that in the years of Georgian oppression in Abkhazia, this was a great victory.

Marina personally selected works for this exhibition, and decided not to include her own works in the exhibition, but to present the works of young Abkhaz sculptors Viktor Ivanba and Yuri Chkadua.

In 1996, the program of the famous journalist Vladimir Zantaria about Marina Eshba was broadcast on Abkhaz television.

Marina herself in the show devoted to her appears in the frame only once and for a very short time, which is sufficient for the viewer to understand the whole inner strength of this person. Gently and thoughtfully she gives a comment about her struggle.

“Almost all the artists who worked here in Abkhazia were sent from Georgia, they received their workshops, houses, apartments, they felt fine, occupied positions. Against this background, I even had some kind of excitement: why did it turn out so unfairly, such talented and young artists of Abkhaz origin were not able to study at school in Abkhazia, studied in Georgian ... why did they had to cripple such talented people? Of course, I completely plunged into this struggle, it can be said, because they [the Georgian leadership] did whatever it took. I felt that I did not want to retreat,” says Marina in this short cut.

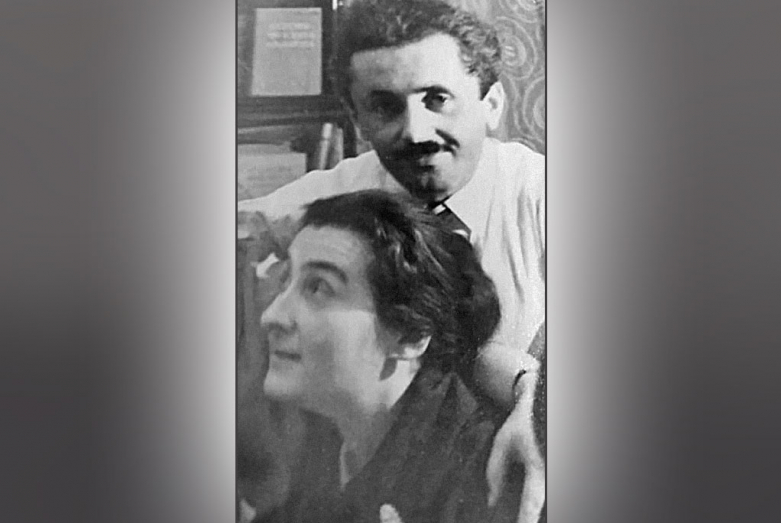

A beautiful woman with a male character

Marina was a sincere and direct person and, as is clear from various facts of her life, she knew how to be friends. Close relations connected her with the family of another prominent Abkhaz political and state figure - Aslan Otyrba, and then with his daughter Alla ... Alla Otyrba, a pianist known in Abkhazia, now lives in Sukhum and works at the Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies named after Dmitry Gulia. She very warmly recalls the older friend who has become an important person in her life.

She and Marina met in the mid-1960s.

“Dad and Marina often met at work. Somehow she came to visit us at home. She immediately attracted attention. She was amazingly beautiful! I was then 15 years old. She was amazingly feminine, she had a soft smile and a very relaxed manner of communication. With such femininity, she had a clear masculine character. With us, children, she never lisped,” recalls Otyrba.

Alla, who later met the entire Eshba family, assures that Marina has shown her decisive character since childhood. Marina’s mother told about it several times.

“Even as a child, living in Moscow, she had determined for herself that she was an Abkhaz woman, - notes Alla and tells the story from the school years of Marina Eshba. - In the [Moscow] school, Marina’s surname aroused interest, classmates asked who she was and where she came from. Marina shared this with her father. He replied that he was Abkhaz, that Abkhazia was his homeland. He added that Marina’s mother is not an Abkhaz, and the girl herself can decide [about her nationality]. Without thinking for a long time, she replied: Dad, I am like you. The next day I went to school and stood up right in class and solemnly declared to the whole class that she was Abkhaz. Then Marina's determination was noted by the teacher.”

Alla and Marina got especially closer in the 1990s, they had a lot in common. The saddest circumstances of their life turned out to be similar: both Alla and Marina lost their sisters.

“She always said she is not a sentimental person. But they had a special affection,” says Otyrba about Marina’s relationship with her sister Lisa.

Eshba went through the hard sick of losing her sister very hardly, which was reflected even in the desire to do what she loved.

“This (the death of her sister - ed.) hid hard the aunt Marina, she did not want to work. Together with my mother, we persuaded her to return to the workshop. I, at her request, went to the workshop with her, but we always came back. Once we were about to leave [from the workshop], as she told me: you go, and I will stay and work,” Alla recalls.

The talent of Marina Eshba has always been noticeable and in demand. Experts in authoritative publications often wrote about this, but the main thing: her works touched simple residents, who might not even be well versed in art. There is a story in her works, there is life in them. And today, decades later, they attract attention to themselves, affecting some personal “string” in people, arousing their personal pain and joy.

Marina Eshba passed away on May 17, 2002 after a short illness. She left, leaving a part of her soul in each of her sculptures, a part of her heart to everyone who once was acquainted with her, leaving Abkhazia and the Abkhaz people the greatest legacy.

You can see the works of the medallist Marina Efremovna Eshba here >>

to login or register.