Tevfik Esench was the last person who knew the Ubykh language. On the eve of the 115th anniversary of his birth, the WAC web information portal visited Esench’s house in the Ubykh village of Haci Osman in Turkey.

Asta Ardzinba

Ubykhs are the indigenous people of the Western Caucasus, related in culture and life to Abkhaz, Abaza and Circassians. Until the end of the Caucasian War in 1864, the Ubykhs lived on the Black Sea coast between the rivers Shahe and Khosta (the territory of modern Greater Sochi - ed.). In the west, the Ubykhs bordered with the Adyg tribe of Shapsugs, and in the east - with the Abkhaz tribes.

Fade into history

The Russian military leader Mikhail Tarielovich Loris-Melikov called the Ubykhs “a warlike and enterprising tribe that always enjoyed special significance among its neighbors.” There was even a belief: to be brave, you have to live and learn from the Ubykhs. Nevertheless, this people, one of the most warlike peoples of the Caucasus, was destined to fade into history.

Refusal to submit to the Russian Empire and move to the Kuban steppes after the end of the Caucasian War forced the Ubykhs to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire.

A number of sources note that their relocation took place very quickly. We can say that for three weeks at the end of April 1864, there were almost no Ubykhs on the territory of the southern slope of the Western Caucasus, between the Shahe-Khosta rivers.

According to various estimates, about 50-70 thousand representatives of this small nation migrated overseas. They settled in a large part of Western Asia from Syria to the Sea of Marmara and the Balkans. Gradually, the Ubykhs lost their national characteristics and their language.

“I don’t know if anyone who knows Ubykh will be found, <...> many tribes of this group rest in the “cemetery of peoples,” wrote the famous Russian Caucasian historian Pyotr Karlovich Uslar in his book “Ethnography of the Caucasus. Linguistics. Abkhaz language.”

This prophecy has come true.

The last of the Ubykhs

In the modern world there is a tendency: languages are dying out. According to experts, most of the languages of the world today are doomed to extinction. This phenomenon can be regarded as a natural “evolutionary” process, but it must be borne in mind that with the loss of language, the culture of the people who are the speakers of this language gradually dies.

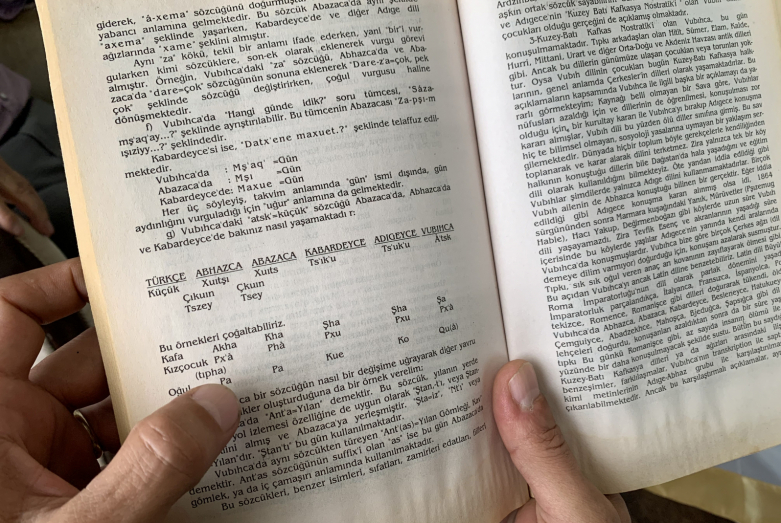

This fate befell the Ubykh language: today it is considered dead. Ubykh language belongs to the Abkhaz-Adyg family. It is unique in its phonetics with 80 consonants and three vowels (short “a”, long “a”, “ы”).

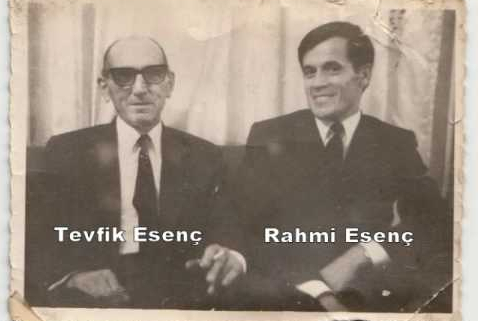

The last known native speaker of the Ubykhs was Tevfik Esench. He was born in 1904 in the village of Haci Osman near the city of Manyas in northwestern Turkey. He belonged to the Ubykh family of Zeyshua. During the reign of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the family received the Turkish surname Esench.

Tevfik Esench managed to convey to the world unique information about the language and culture of the Ubykh people. Possessing a wonderful memory and clear thinking, Esench told scholars a lot not only about the language, but also about the mythology, culture and customs of the Ubykhs.

Esench was the informant of the famous French linguist Georges Dumézil. Their long-term cooperation led to the production of scientific works that are extremely valuable for the study of the Ubykh language and culture.

Knew the language perfectly

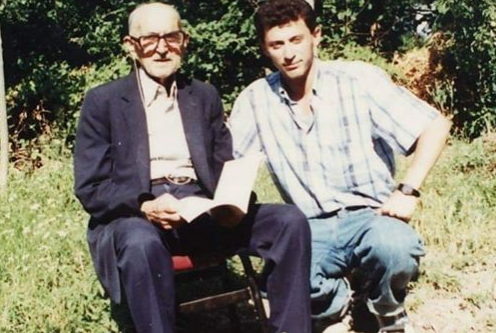

Doctor of Philology, Professor Viacheslav Chirikba is one of the last foreign scholars who worked with the last native speaker of the Ubykh language Tevfik Esench.

Their meeting took place in 1991. As Chirikba notes, Esench did not just know the language of his ancestors, like some other old men who remembered words and phrases in Ubykh. It was his native language, he was fluent in it.

“I managed to work with him for about four hours. I wrote down a story about his family in the Ubykh language, which I later translated into Turkish, [wrote down] various texts and words,” the scholar said.

In another interview, Esench expressed one version of the disappearance of the Ubykh.

“The Ubykhs stopped speaking their native language in Turkey because they thought it was bad manners to speak a foreign language among the Turks,” he said.

Fatal cause of extinction

However, other more significant factors influenced the disappearance of the Ubykh language. As Viacheslav Chirikba notes, the Ubykh language in the Caucasus was “in agony” and could not withstand competition with the Abkhaz and Adyg languages. Chirikba recalls that this was also pointed out by Pyotr Uslar in the 19th century (Pyotr Uslar - a Russian military engineer, linguist and ethnographer, one of the biggest Caucasian scholars of the 19th century - ed.). A fatal circumstance was that the Ubykhs did not settle compactly in a foreign land, but were scattered throughout Turkey.

“From Trabzon to Bursa, small Ubykh villages were scattered. They were small enclaves surrounded by Turks, Circassians, Abkhaz, Kurds and other peoples. Where there were more, the language was preserved until recently,” said the professor.

Thus, the Ubykh language was preserved for the longest time in the west of Turkey in the Balikesir region and in the central part of the country in the Sapanca region.

Despite the tendency to lose culture along with language, it would be wrong to say that the Ubykhs lost their national characteristics along with the loss of language, Viacheslav Chirikba is confident.

“Ubykhs in Turkey consider themselves Caucasians, remember their origin well, traditionally celebrate weddings. They preserved tunes and melodies, dance beautifully in the Caucasian way. Yes, they have lost their language, but they feel their connection with their homeland and treat the Abkhaz and Adyg as their brothers,” says the scholar.

“I was at home and can die peacefully”

In 1990, Tevfik Esench traveled to the Caucasus: Nalchik, Sochi and Krasnaya Polyana.

“Once upon a time, in my youth, I loved to close my eyes and imagine my homeland as my grandfather described it to me. Mountains, sea beyond the mountains and everywhere, everywhere trees; plane trees, yew-trees, shrubs ... Now I see that it is exactly the same as I imagined it ... It is a pity that my ears can already hardly hear, my eyes can hardly see, and my legs can poorly walk. But still, I can now die calmly. I was at home,” Esench will say during this trip.

It was Tevfik Esench who served as the prototype of the protagonist of the wonderful novel of the Abkhaz poet and writer Bagrat Shinkuba “The Last of the Departed,” published in the 60s of the last century. This novel is translated into Turkish entitled “The Last Ubykh” (Son ubih).

“Vubıh dilini ölümsüzlestiren bu dili yazıp konusabilen son Vubıh”, which means “Here lies Tevfik Esench, the last person who knew the language of the Ubykhs.” It is this inscription that is carved on the tombstone of Tevfik Esench in the cemetery of his native village of Haci Osman.

In the house of Tevfik Esench

Today, the Ubykh village of Haci Osman consists of about two hundred small courtyards. Most of them are empty. However, some residents who have long moved to the city come here for the summer. About two dozen people live here, mostly retirees.

Tevfik Esench’s house is in the very center of the village. Now his son Zeki lives here.

In the hall of the house are photographs of family members: Zeki's daughter lives in the United States, and her son in Singapore. On the wall there is a portrait of his great-grandfather, an old man named Kukush. Thanks to him, the maternal grandfather, Tevfik Esench knew his native language and Ubykh folklore. Kukush was born in Ubykhiya, but his descendants are already in a foreign land.

An honorable place on the wall is occupied by the portrait of Georges Dumézil. Tevfix Esench and a French linguist have spent many hours at work in this house.

“Father and Dumezil worked together both in Istanbul and here. They loved to sit in the garden,” says Zeki.

And here is a tree that is surrounded by a vine. Ubykhs did not make wine in Turkey because of the Islamic ban on alcohol, and the tradition of growing grapes on a tree has been preserved. But this vine is not ordinary.

“My ancestors brought this grape from the Caucasus, - Zeki explains. - They hid the twigs in a breast pocket. That’s all they managed to bring from the Caucasus.”

In Haci Osman today there are no Ubykhs who know Ubykh. They can remember separate words, but they, can no longer speak a language coherently. The same picture is in other Ubykh villages in Turkey. According to rough estimates, today in the country there are about ten thousand Ubykhs, who, however, do not remember their native language.

to login or register.