The famous Caucasus expert Georgy Dzidaria entered the history of Abkhazia not only as an outstanding scholar, but also as a co-author of the famous “Letter of the three”.

Arifa Kapba

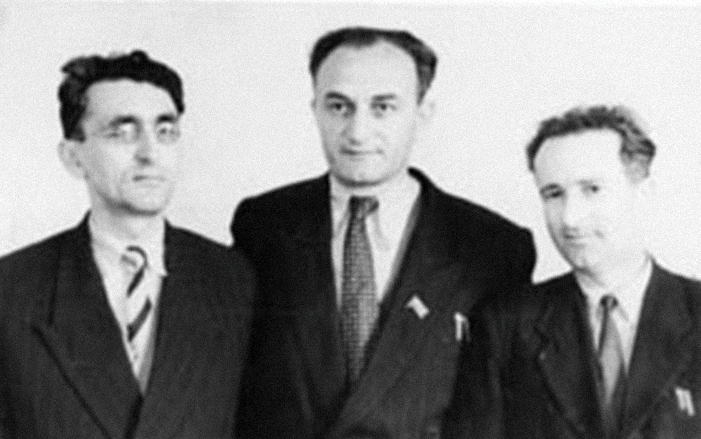

Georgy Dzidzaria is an eminent Caucasian historian, scholar, doctor of historical sciences who has devoted his entire life to studying the history of his native land. But in Abkhazia, he is inscribed in gold letters also because in the 1940s, with the beginning of the active “Georgianization” of the Republic, he was not afraid to stake his fate and career, acutely condemning the changes that began in Abkhazia in the famous “Letter of the three ”, which was written together with the poet Bagrat Shinkuba and the scholar Konstantin Shakryl.

Interest in history

He was born in the village of Lykhny on May 6, 1914. Georgy’s father, a peasant Alexey Dzidzaria, was part of the “Kiaraz” peasant squad organized by Nestor Lakoba (Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Abkhaz ASSR - ed.). Mother, Elizabeth (Ziza) Davidovna, was the sister of one of the “Kiaraz” members, the famous revolutionary Ignatius Vardania. At the age of four, the boy lost his father and was raised by his mother.

From the age of ten, Dzidzaria studied at the Gudauta orphanage, and in 1929 entered the Sukhumi High School named after Nestor Lakoba. While still in school, he showed an interest in the history of his native land - thanks largely to teacher Alexey Vsevolodovich Fadeev, who advised him to collect facts, documents and physical evidence on which to draw conclusions, and then write works.

After graduating from school in 1934, the young man enthusiastically engaged in history went to the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature.

In his autobiography, Dzidzaria writes: “Here I happened to learn from such prominent Russian historians as academicians Yuri Vladimirovich Gotye, Evgeny Alekseevich Kosminsky, Mikhail Nikolaevich Tikhomirov, Sergey Vladimirovich Bakhrushin, Isaak Izrailevich Mints and others, who played a big role in my formation as a historian.”

Already in his student years, Dzidzaria was particularly interested in the problems of the history of Abkhazia in the 19th century.

After graduating from high school in 1939, Dzidzaria returns to Abkhazia and works first as a junior, and then as a senior researcher at the Abkhaz Institute of Language, Literature and History named after academic Marr (now the Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies named after Dmitry Gulia - ed.). In 1953, he will become deputy director of the institute for science, and from 1966 until the end of his life he will head it.

Dzidzaria combined research activities with the teaching of historical science. He headed the Sukhumi Pedagogical Institute named after A. M. Gorky from 1957 to 1966, and he taught there since 1939. It was on his initiative that the course on the history of Abkhazia was introduced at the history department of the institute. When the Abkhaz State University was established in 1979, Dzidzaria headed the department of history, archeology and ethnology of Abkhazia and began to teach a course on the history of Abkhazia of the 19th - early 20th centuries.

“Georgy Alekseevich Dzidzaria is one of those who stood at the origins of the formation of the Abkhaz historical science, whose foundations were laid in the absence of professional national historians, historiographic tradition and poor source-study base,” writes the historian Arvelod Kuprava about Dzidzaria.

“Letter of the three”

Georgy Dzidzaria was not only an outstanding scholar, but also a great patriot. Like many other representatives of the intelligentsia, he was deeply worried about what happened in Abkhazia since the death of Nestor Lakoba - an attempt to “Georgianize” the Republic, a ban on studying in schools in the Abkhaz language, an unfair personnel policy, leaving representatives of the Abkhaz nation “out of work”. In 1947, they, together with the famous writer and poet Bagrat Shinkuba and Caucasian scholar Konstantin Shakryl, wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (Central Committee of the CPSU (B.). The authors described the situation in detail and asked the country's top leadership to pay attention to this.

Among the problems they listed were such as the “reorganization” of the Abkhaz schools, in which instruction began to take place in the Georgian language, an acute reduction of the number of Abkhaz schools, a change in local toponymy (geographical names - ed.) in the Georgian fashion, ignoring Abkhaz literature and the impossibility of being printed for Abkhaz writers, the absence of persons of Abkhaz nationality in the highest party and leading seats and at the same time attracting people from Georgia to these positions, the massive settlement by Georgians.

The letter had the effect of a bombshell, and its authors were subjected to the most severe criticism.

“The authors of the letter were severely punished - they were incriminated with an attempt to misinform the Central Committee of the CPSU (B) and slander the Abkhaz party organization. Lately, they were labeled as “bourgeois nationalists” and “fascist elements”, this continued until 1953,” noted in the book by Oleg Bgazhba and Stanislav Lakoba,“The History of Abkhazia from Ancient Times to Today”.

Arvelod Kuprava notes that this letter could not but play its role in the life of Georgy Alekseevich - for a long time after its signing the scholar had to live and work in an atmosphere of harassment.

“At the same time, we had to overcome material difficulties, moral and psychological pressure. Until 1956, his family, where four children grew up, lived in the same room at the dormitory of the teacher's college. After the famous letter of 1947, Georgy Dzidzaria, Bagrat Shinkuba, Konstantin Shakryl were subjected to cruel persecution. At the beginning of the 1949 academic year, Georgy Alekseevich was suspended from lecturing at the pedagogical institute - “political distrust was expressed,” then he was twice categorically ordered to “release the occupied living space in the lecturers' hostel”; “In the event of non-release,” the director of the Institute, R. Tsulukidze, threatened “to transfer the case to the prosecutor’s office,” writes Kuprava.

Scholar and statesman

Georgy Dzidzaria has more than 400 published works, among them over 150 scientific papers and about 50 monographs.

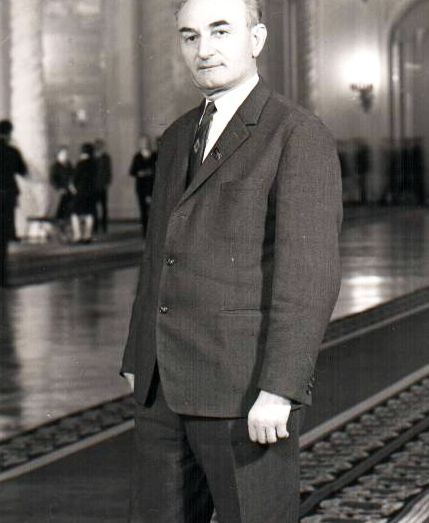

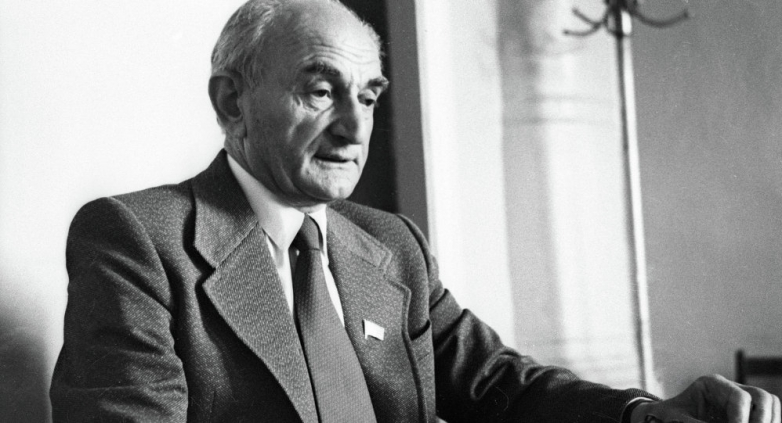

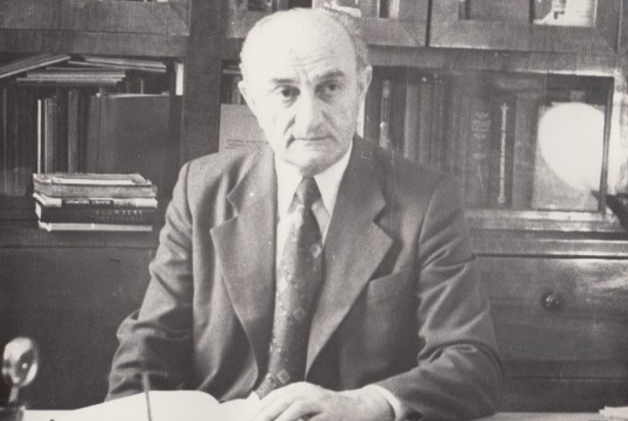

Here is an indicative characteristic of Dzidariya the scholar, published in the newspaper “People’s Party of Abkhazia” on May 4, 1999: “Tall and slim, Georgy Dzidzaria, when he sat at his working desk, on which he constantly had books, documents, manuscripts and other papers, towered above them with his strictly straightened stature and broad shoulders, which served as proof of his strong physical build, and a benevolent smile spoke of his spiritual attitude. In the office, he always stood up to meet any guest, visitor. As soon as he got involved in the conversation, immersion into thought immediately went off his face, and he led a lively conversation. When his colleagues came to him, he usually liked to talk with them, sometimes he did it while walking around the office, did not miss an opportunity to cheer up in a good initiative or discourage from an undesirable step.”

Dzidzaria is a recognized expert in the history of Abkhazia of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His scientific works are considered textbooks and recognized in the widest scientific circles.

“Georgy Alekseevich Dzidzaria is the first Abkhaz scholar who has scrupulously studied the social structure of the Abkhaz society of the XIX century. He gives <...> a detailed definition of the social person and social status of each social subject of the 19th century Abkhaz society,” writes historian Arvelod Kuprava.

His work on the so-called “strange uprising” of 1866, the scientist wrote in the most difficult times, which followed after the letter to the Central Committee of the CPSU (B). The uprising was triggered by the illiterate policy of Russian officials who did not understand the intricacies of the local mentality and announced in Abkhazia the abolition of serfdom (legal relations, the essence of which was reduced to the dependence of the peasant on the owner of the land on which he lived and which he cultivated - ed.). But, unlike Russia, serfdom never existed here. That is why the uprising was called “strange”: instead of a joyous reaction to the announcement of the decree about their release, outrage and peasants, who considered themselves free, and princes, became, as the decree indicated that they owned “slaves”. The book “The Uprising in Abkhazia of 1866” was published in 1955 and was the first scientific monograph of Georgy Dzidzaria, which brought him fame in the scientific world.

The monograph “Mahajirism and the problems of the history of Abkhazia of the XIX century” stands apart in the research works of the scientist. Specialists rightfully call this book “the chronicle of the 19th century Abkhaz tragedy and the monument to the victims of the Caucasian War.” The work is based on a scrupulous study of a large number of documents and memoirs from the archives of various cities - Moscow, Leningrad, Tbilisi, Krasnodar, Sukhum.

Another significant contribution of Georgy Dzidzaria to the study of the history of Abkhazia was the fundamental monograph “The formation of the pre-revolutionary Abkhaz intelligentsia”. In this work, the scientist talks about prominent representatives of the Abkhaz intelligentsia, which was formed at the turn of the century and made a great contribution to the social and political life of Abkhazia. For this work in 1980, Georgy Dzidzaria received the Dmitry Gulia State Prize of Abkhazia.

Georgy Dzidzaria was one of the prominent and authoritative public and state leaders of the republic. In 1957 - 1959, he served as the Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Abkhaz ASSR, and from 1975 until the end of his life - Chairman of the Supreme Council of Abkhazia. Three times he was elected deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

“Leaving the pier, goes to sea”

The fact that Georgy Dzidzaria’s entire life was subordinated to science and social activity was quite acutely felt in the family, with whom he simply did not have time to communicate. Georgy Alekseevich Dzidzaria and his wife Olga Alexandrovna Geria raised four children - the daughter Annette and three sons - Astamur, Gudisa, Adgur.

It is interesting how his son Adgur Dzidzaria perceived his father during his childhood.

Here is how he describes his feelings: “When [the father] was going to work in the morning, Mom would go out on the porch behind him, so that, already in a check, waving a wardrobe brush over clothes. It looked like a ship, leaving the pier, goes to sea.”

The family has always believed that the academic and social activities of Georgy Alekseevich are a priority, that this is a “deliberate sacrifice”. “It was customary for us that, coming from work, the father continued to work in his office, - the son recalls. - When I grew up I understood that work at the institute, where he was a director, and the historical science in which he was engaged are not the same thing. He gave all of himself to science, so he “got it” wherever he could: he stayed with papers late, taking materials with him on any trip, including when he went on holiday. As far as I can remember, I always had the feeling that my father was busy with very important affairs. And these affairs were dominating. Even us, the family, could not compete. Yes, we did not try, because somehow it was settled so. There was an understanding that everyday comfort and coziness are not at the head of human activity, that there are higher, or more important, goals.”

The scholar never had time for any household chores: even if he was engaged in them, it was more likely to “give rest to the head” rather than for practical reasons. Not being able to pay much attention to family and children, Georgy Dzidzaria, however, understood how important it is to give them access to a good education, to reading books. “Of course, my father tried as best he could for us, - notes Adgur Dzidzaria. - He subscribed to almost all the newspapers and magazines. We had book collections for children. [There was] a radio receiver and a record player with a bunch of records, including new ones at that time, with recordings of Abkhaz folk ensembles released during the post-Stalin period.”

A large family of Dzidzaria could not afford to go to rest somewhere far away, most often it was a trip to the native village of Lykhny.

The son of the scholar recalls that he loved to listen to his father’s stories as a child when he was sent to mountain pastures as a boy for the summer holidays: “He lost his father very early. He studied at the boarding school. When he returned home for the summer holidays, where there were children, his grandmother sent him to the mountains with the shepherds. I loved when he told some episodes from the shepherd's life. He, besides the fact that knew the Abkhaz well, knew the shepherd - or hunting language - now I can’t say for sure.”

The great scholar and true patriot of his homeland, Georgy Dzidzaria, passed away in 1988, having outlived his wife for only 26 days. His grave is located on Lykhnashta - a large clearing in his home village of Lykhny.

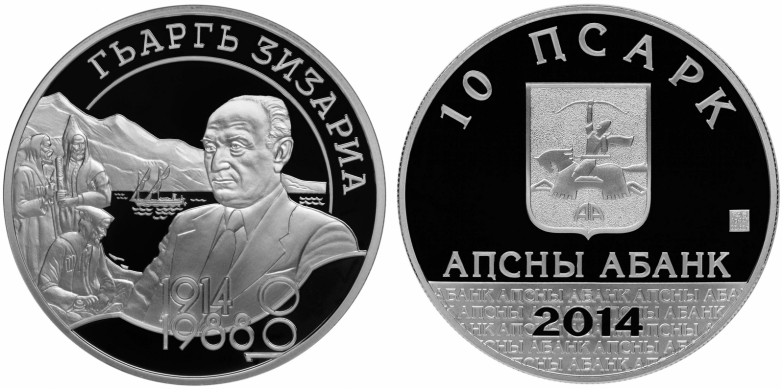

The State Dzidzaria Prize in Science was established in honor of the scholar in 2004. Streets in different towns of Abkhazia are named after him, large scientific conferences are held in his honor. In 1995, the state-owned company “Apsnyeimadara” issued a special postage stamp depicting a scientist, and in 2014, commemorative coins were issued for the 100th anniversary of the writer.

to login or register.