He stood at the origins of the national liberation idea of the Abkhaz people, created the first Constitution in the history of Abkhazia, was convinced that the future of the Republic is in alliance with the mountaineers of the North Caucasus. Simon Basaria could not be forgiven such free-thinking and initiative.

Arifa Kapba

He was at the origins of the national liberation idea of the Abkhaz people, created the first Constitution in the history of Abkhazia and was convinced that the future of the Republic was in alliance with the mountaineers of the North Caucasus. Simon Basaria could not be forgiven such free-thinking and initiative.

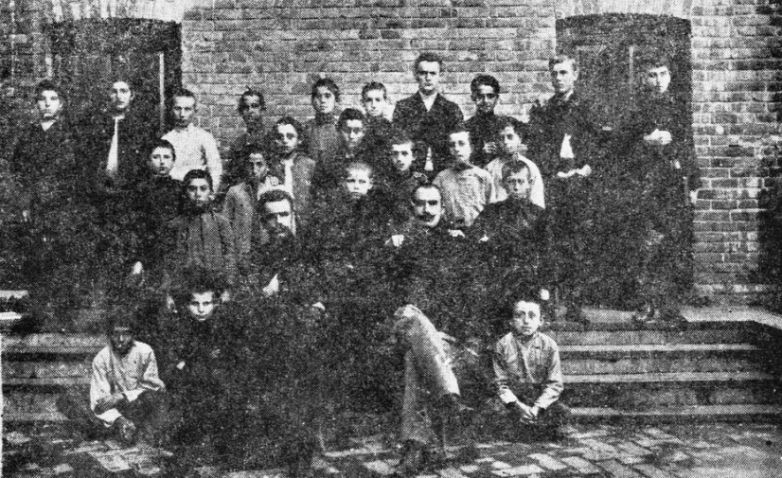

Simon (Mahaid) Petrovich Basaria, a well-known teacher, local historian, scholar, publicist, public and political figure, was born in the village of Kutol on December 8, 1884. He was the son of an ordinary peasant. At the age of ten, he was sent to study at the parish school in the village of Bedia and then he graduated from the Sukhum Gorsky School. Exemplary behavior and excellent knowledge allowed him to enter the Transcaucasian Seminary in the Georgian town of Gori in 1897.

Outside the homeland

After graduating from the seminary in 1902, eighteen-year-old Simon Basaria, at the invitation of the Caucasian school district, went to work as a teacher to the Circassian village Kassievsky of the Kuban region. There he worked at a school, teaching Circassian children Russian language and geography. But a year later he was transferred to the Armavir Higher Primary School.

Staying in the North Caucasus is a significant period in the life of Simon Basaria, the doctor of historical sciences Yuri Anchabadze believes: "He was deeply engaged in self-education, read a lot, attended various training courses, including in other towns of the region, traveled, for example, to Anapa for this, and in 1908–1909 he was in Moscow, where he attended classes of the Society for the Promotion of Technical Knowledge."

It happened so in the life of Basaria that his experience, brilliant knowledge and worldview - all this was formed not only in Russia, but also abroad. In 1910, thanks to the Society for the Promotion of Technical Knowledge, he went to study the formulation of primary education in Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Switzerland. According to Professor Georgy Dzidzaria, he also visited North Africa, Turkey, not to mention the fact that he traveled all over the entire Russian empire.

It is worth noting that even being far from home he never stopped thinking about it. Whatever knowledge he mastered, whatever ideas he was filled with - no doubt he projected all this onto his future activities in his native land. He wanted to have a connection with Abkhazia and to know what was going on there. Evidence of this is his letter to a well-known public figure in Sukhum, educator Andrei Chochua.

"Friend," wrote Basaria to Chochua, "let's start a correspondence, because we once loved each other. Write about everything. I serve in the busiest place of the Caucasus. Armavir is the cultural center of the North Caucasus." According to Professor Georgy Dzidzaria, Simon Basaria regularly received newspapers and periodicals from Abkhazia.

Basaria - publicist

In 1910, Simon Petrovich began his journalistic activities. He becomes a correspondent for the Petersburg Academy of Sciences and is published in such newspapers and magazines as "Responses of the Caucasus", "Voice of the Caucasus", "Black Sea Bulletin", "Sukhum Bulletin", "Sukhum Leaf" and others. Most often, he signs his publications with the pseudonym Simon Apsua or Mahaid Apsua.

The topic of almost all of his publications is the perspectives and the fate of the long-suffering Abkhaz people and Abkhazia. None of the really serious for his homeland topics could bypass him.

Thus, in the article "The Highlanders of the Caucasus in Turkey", published in the newspaper "Sukhum News" in May 1913, he writes: "The migration was spontaneous: the tribes left without realizing where they go and why ... the highlander left his home and sacred village, where his ancestors lived a happy life. Inexpressible grief on his face, he took all his beloved with him, his sad, thoughtful horse is with him, his favorite animal — a lamb, his son and a daughter are with him and a sacred weapon, an obedient performer of his will."

These articles were not based on abstract reflections, but on very specific facts: he met in Istanbul with the Abkhaz, who left their homelands and with pain in their hearts recalled their own "country of the soul" - Apsny.

"His correspondence is imbued with tireless thoughts about the best share for his fatherland and its residents, hopes for future positive changes," Yury Anchabadze notes. - The subject of his concern was: the state of the medical business in the region, the underdevelopment of the school network, the inadequacy of the social sphere. Basaria rather sharply attacked the local authorities, accusing them of negligent inaction, indifference to the needs of the indigenous population, the "police rampant".

Home with the idea of freedom

In 1917, when a revolution broke out in the Russian empire, the most favorable situation developed for Simon Petrovich to finally return to his homeland and try to fulfill those thoughts and aspirations he expressed on paper. And he comes back - with the thought that Abkhazia should change forever.

This time has become one of the most important periods in the history of Abkhazia. The Russian Empire was collapsing and Georgia was trying to get out of it, leaving at the same time in its composition the "tidbit" - Abkhazia. Simon Basaria was against such a perspective.

In August 1917, the All-Abkhazian congress of clergy and laity was held. Simon Petrovich Basaria actively participated in the congress and was able to promote his idea of autocephaly of the Abkhaz Church, which in fact made it independent of the Georgian clergy. This was the first step that separated Abkhazia from Georgia, but Basaria understood: the road is long and the most difficult is yet to come.

Head of the Abkhaz National Council

On November 8, 1917, another All-Abkhaz Congress took place. To prepare for the congress, Basaria and his supporters did a great job: they traveled to many Abkhaz villages, convincing people that they should gather in Sukhum on November 8 to say to everyone: the Abkhaz want to be free.

Simon Basaria, speaking before the delegates, read out the Declaration of the Congress, which he himself drafted. It stated that "in the revolution, the Abkhaz people see only freedom of national self-determination". The most important outcome of the congress was the formation of the Abkhaz National Council and the adoption of the first in the history of Abkhazia Constitution. Simon Petrovich Basaria himself was elected Chairman of the Abkhaz National Council (ANC), as was to be expected.

The Council immediately makes decisions that would strengthen the Abkhaz’s desire for their own statehood and independence. In one of the decisions taken by the ANC, it says: "All lands on the territory of Abkhazia: from the Mzymta River to the Ingur River, from the Black Sea coastline to the Caucasus Mountains, with all their natural wealth, are to be an integral part of the Abkhaz people and other peoples living in Abkhazia and having common property on a par with the Abkhaz."

"The external vector" of Abkhazia Basaria saw only in cooperative unity with the mountaineers of the North Caucasus. This idea was supported by the Congress, but the clouds over Abkhazia were gathering. May 26, 1918 Georgia declares its independence. The Abkhaz National Council is divided according to foreign policy orientations. In the end, Simon Basaria is removed from the management of the Council. Persecuted by the Georgian Mensheviks’ defamation, Basaria is forced to leave Abkhazia for a while, but in 1920 he returned with the condition "not to engage in political activity".

However, after the Soviet power was established in Abkhazia in 1921, Basaria himself did not aspire to engage in politics: he did not have much sympathy for the Bolsheviks, according to Yuri Anchabadze, "he was not ready to sing odes to them". However, this did not mean that he stopped intently following what was happening. Welcoming the date of March 31, 1921, when the

independent Abkhaz socialist republic was proclaimed, Basaria was discouraged in December of the same year, when the Abkhaz and Georgian socialist republics united on federal basis on the 16th. Subsequently, Basaria often criticized the authorities on many important issues, but he was not directly involved in politics.

Out of politics

Leaving politics aside, he worked fruitfully in the field of science, education and culture. In 1923, the main work of Simon Petrovich Basaria as a scientist, "Abkhazia in geographical, ethnographic and economic terms," was published.

Despite the fact that Professor Georgy Dzidzaria subjected this work to rather harsh criticism, noting that it made a number of significant mistakes, the book still has important historical and cultural significance. Yury Anchabadze agrees with this: "It turned out to be the first edition in which the ethnography of the Abkhaz was presented in a monographic outline with coverage of, if not all, then at least most of the sides of their everyday culture. The sources of the book were not compilation reviews of previous literature, but independent field observations, which were recorded by the author for a number of years. In the preface to the book, Simon Petrovich wrote that he was dreaming of scientific literature, "written by the sons of Abkhazia, who could give accurate information about their homeland and people."

Simon Basaria played a crucial role in the upbringing and training of teaching staff: he was a teacher, deputy director and director of the Abkhaz Pedagogical Technical School. He paid great attention to the creative youth. It was during his time in the technical school that a literary circle appeared, where at that time a third-grade student of the technical school, and then the great Abkhaz poet Iua Kogonia, read his own poems for the first time in public.

It is difficult to list all the cases in which Simon Basaria had a hand. For example, his enthusiasm for the folk song led to the fact that he helped the famous collector of folk musical motifs Konstantin Kovac in his work, and his local lore research turned into fascinating notes about the survivors of Abkhazia: in addition to their biographies, they contain unique material - pictures of old men. Simon Basaria is also the author of one of the first textbooks on the geography of Abkhazia, which has gone through several editions.

The life of Simon Basaria ended tragically. Somehow miraculously escaping from repressions in 1937, when the elite of the Abkhaz intelligentsia was shot, Basaria was arrested in 1941. He was accused of involvement in the activities of some counter-revolutionary organization. Moreover, he figured in the case as the "head of the organization." And then everything went according to the scenario, which in those years was almost the same for the repressed: departure to Tbilisi, the most severe interrogations and execution.

Describing the personality of Simon Petrovich Basaria, Professor Georgy Dzidzaria writes: "Simon Petrovich showed strict demands on himself and others, sensitivity and attentiveness to ordinary people. The bureaucratic habits were deeply alien to his nature; he was a direct and principled man."

to login or register.