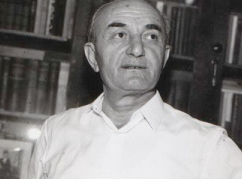

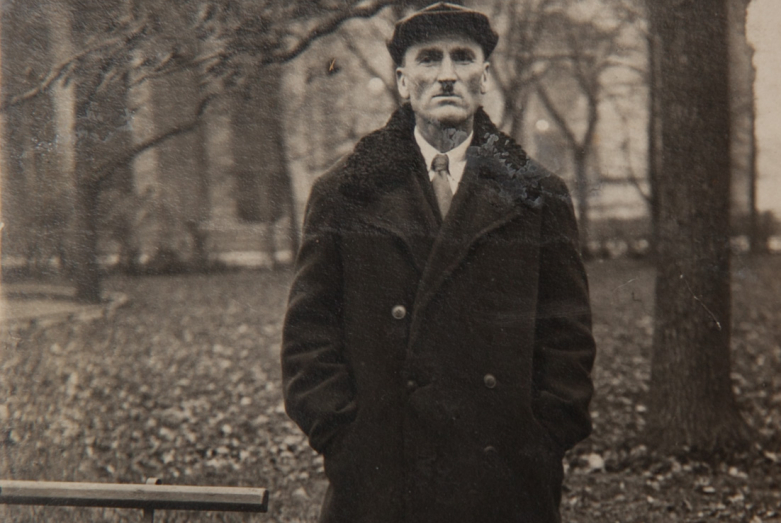

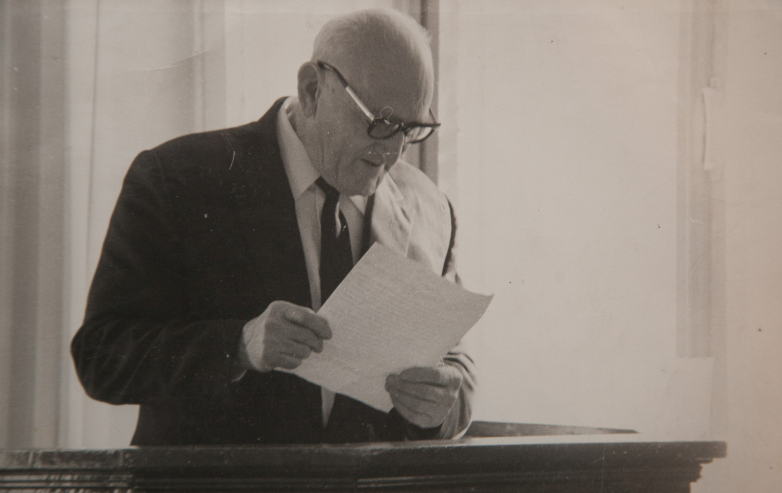

On May 20, the outstanding Abkhaz enlightener, winner of the Dmitry Gulia State Prize Konstantin Shakryl would have turned 120 years old.

Said Bargandzhia

The history of Abkhazia is a constant struggle to preserve its originality, which in different years has flowed into the struggle for the survival of the Abkhaz as an ethnic group. However, ultimately our history is, as a result, always a victory. Yes, we achieved it at a very high cost, but it was a true victory. And always, at all times, the symbols of this victory were outstanding representatives of the people.

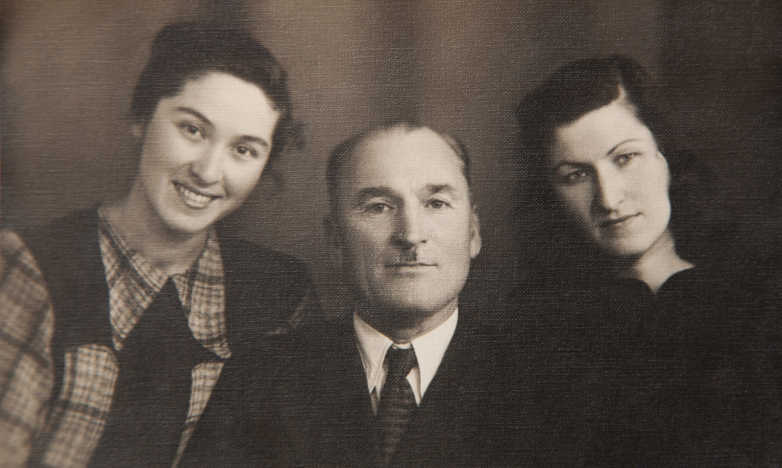

Such people were Konstantin Shakryl and his close relatives: elder brother Platon Shakryl and niece Tamara Shakryl. None of them is no longer alive, but they left a strong spirit and unshakable faith in the success of works for the benefit of the motherland.

The current successors of this brilliant family are the two granddaughters of Konstantin Shakryl, Galiya and Esma Kalimovs. Today they live in two cities, being either in Sukhum or in Moscow. During the Patriotic War of the people of Abkhazia, from its first days, they began to wage their struggle - on the information front, working in the Moscow press center and informing the whole world about the atrocities that took place in Abkhazia.

Student, teacher, scholar

Konstantin Shakryl was born on May 20 in 1899 in the village of Lykhny, Gudauta district. In 1909, he went to the school of the Dzhirkhua village, where at that time his elder brother, later known educator and teacher Platon Shakryl, was teaching.

Galiya Kalimova says that her grandfather went to school only when he was 12 years old, because his mother was very sick and he had to help with the housework. So the childhood years became for Konstantin an elementary school of life.

“Grandpa was very economic. He knew how to do everything around the house and especially cooked well. He made homemade red wine and had a vineyard. Probably, all this is due to the fact that since childhood, because of the illness of [his] mother, he was accustomed to independent living,” Galiya believes.

After school, Konstantin entered the Lykhny two-year school, which he graduated in 1917. In the same year he entered the Sukhum Teacher's Seminary. In 1921, Konstantin Shakryl began working as a teacher in the Lykhny school, and since 1924 - in the Abgarhuk one (village in the Gudauta district - ed.)

Working in Lykhny and Abgarhuk schools, he tried to do everything possible in order to improve the learning of Abkhaz language and literature by children. It is hard to imagine now what efforts it cost Konstantin Semenovich to teach them without textbooks. At first, he had to instill in children a love for native literature with the help of stories, poems, fables, articles published in the pages of the first Abkhaz newspaper “Apsny”.

Konstantin Shakryl himself has always been a craving for learning. In 1932, he entered the university and became a student of the history and philology department of the Sukhum State Pedagogical Institute, which he graduated in 1936.

After that, Shakryl was invited to the post of research associate of the Abkhaz Research Institute of Language and History named after academic Marr (now the Abkhaz Institute for Humanitarian Studies named after Dmitry Gulia - ed.), in the same year he was appointed head of the language department.

At the same time, the young scientist gave a course of lectures at two institutes: the Sukhum Pedagogical and the Abkhaz Teacher Training Institute. In 1947, Konstantin Shakryl successfully defended his thesis for the degree of Candidate of Philological Sciences at the Institute of Language and Thinking of the USSR Academy of Sciences in Moscow named after Marr, and in 1970 became a doctor of philological sciences after defending a thesis at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

However, the research and pedagogical activity of Shakryl was interrupted during the period of rampant Beria reprisals (in the 1930s, representatives of the Abkhaz intelligentsia were persecuted. Many were repressed, and some were executed without trial or investigation - ed.).

Fearlessness letter and its consequences

In all secondary schools of Abkhazia, within the framework of a course on the history of the Republic, schoolchildren are told about a letter to the Central Committee of the All-Union Bolshevik Communist Party written by Abkhaz scholars Georgy Dzidzaria, Konstantin Shakryl and Bagrat Shinkuba in February 1947.

Years later, some historians call the famous letter a cry of despair, and all because these three eminent scholars, without fear of the consequences, laid out in it the pain of the Abkhaz people. They told in a letter about the atrocities and oppression of “all Abkhaz” by the dominant Georgia in those years. The consequences did not take long: all three had their party cards taken away, which automatically made them outcasts in the society.

But what the history books will not tell is that in those terrible years for Abkhazia, even contact with people like Konstantin Shakryl could turn into a tragedy.

The Shakryl family has already faced the consequences of persecution. Back in 1937, Konstantin’s brother, Dmitry Shakryl, was repressed; he wrote letters to his house asking him to find out the reason for his expulsion. He never returned to his homeland. Relatives do not know how his fate was, he is considered missing.

And, as Galiya Kalimova testifies, very many people who once knew their family closely knew that after the letter they first distanced themselves, and then stopped communicating altogether: it was dangerous. Subjected to persecution for a principled and uncompromising position, Konstantin himself was soon alienated from his native land.

“It was summer. Grandpa went to the store for a beer. I saw that someone was watching him. He went to one store, then to another, but that person literally followed him. He, fortunately, managed to leave. Then he realized that his life was in real danger. It was decided to fly to Moscow,” says Shakryl’s granddaughter.

It was impossible to leave without the approval of the party, and for some time Shakryl became a hostage in his hometown. Warned by friends who had access to information that the danger to his life really existed, he was forced to leave the borders of Abkhazia secretly. This happened two years after signing the letter.

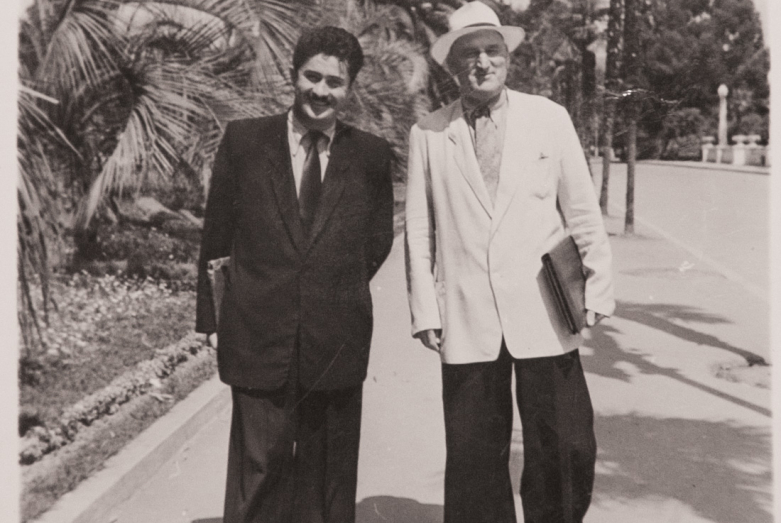

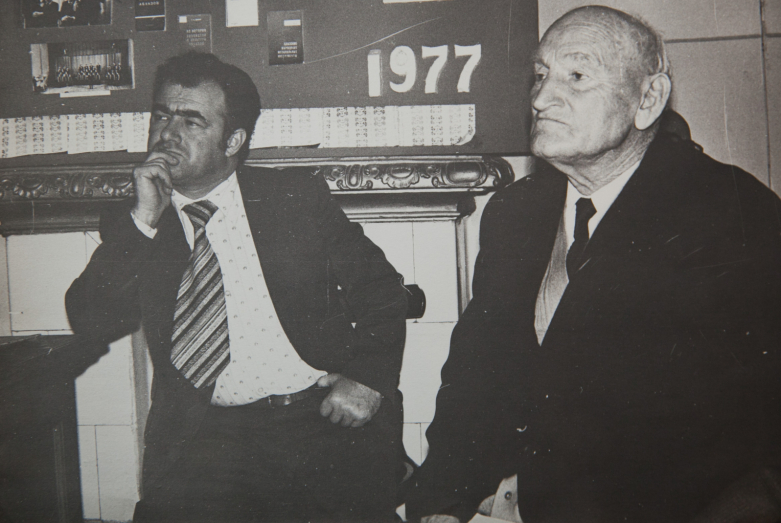

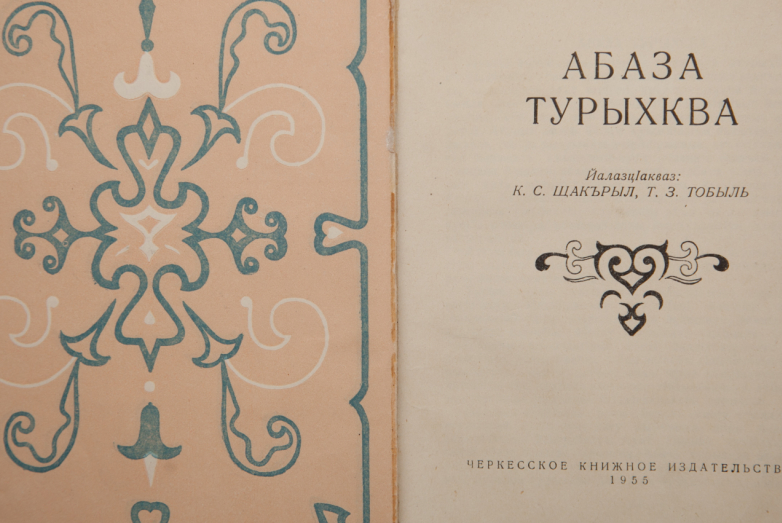

From 1949, Shakryl began working as a senior researcher at the Moscow Institute of National Schools of the RSFSR Academy of Pedagogical Sciences, and in 1951 he was sent to Cherkessk, where he worked first as deputy director, and then as director of the Cherkess Research Institute. Only six years later, in 1955, at the request of the Abkhaz Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia and the Council of Ministers of the Abkhaz ASSR, he was transferred to the Abkhaz Institute of Language, Literature and History (now the Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies named after Dmitry Gulia - ed.). Shakryl was again appointed head of the language department, which he managed until 1976. Until the last days of his life he worked there as a senior researcher.

Scientific, pedagogical and public merits

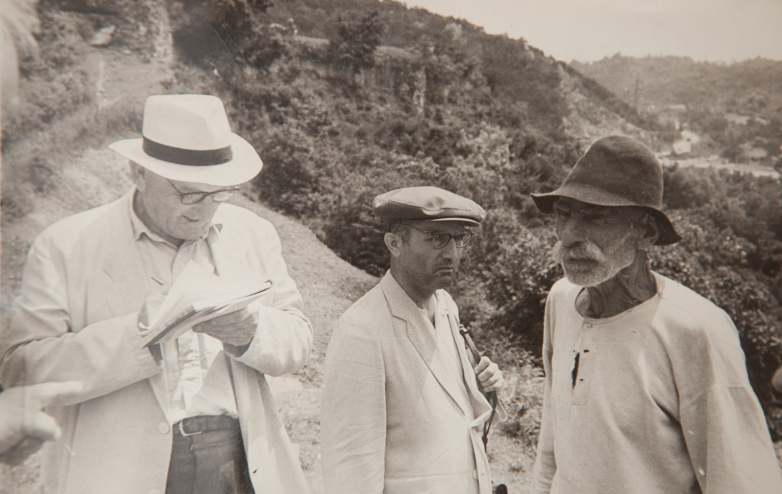

Already in our time, the director of the Abkhaz Institute of Humanitarian Studies, a member of the Supreme Council of the World Abaza Congress, Arda Ashuba and Doctor of Philology Leonid Samanba are studying the works of Konstantin Shakryl and compiling his biography.

Leonid Samanba knew Konstantin since childhood. They lived next door.

“It was the brothers Platon and Konstantin Shakryl who influenced my choice of profession. I can safely call Konstantin Semenovich as my mentor. He was much older than me. I often visited their homes, listened to [their] conversations. They had an incredible family! They stood up even when a child entered the room, believing that it was necessary to set the correct example,” Samanba recalls.

In the preface to his work on Konstantin Shakryl, Arda Ashuba and Leonid Samanba pay great attention to the educational work of the scholar.

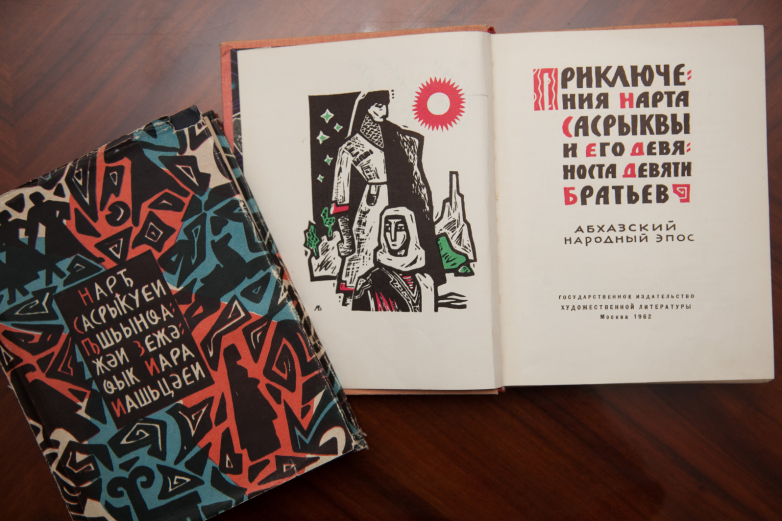

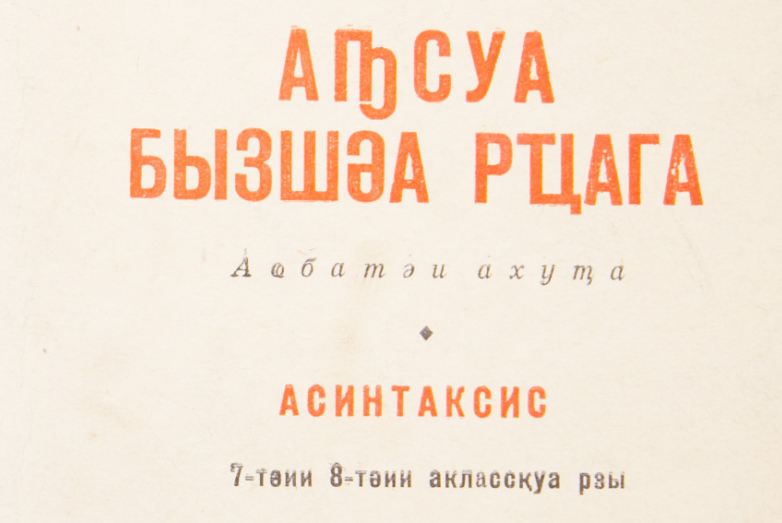

“As a young researcher at the AbNII in 1938, he compiled the first Abkhaz language study textbook for the Abkhaz language for secondary schools - phonetics and morphology for grades V-VI. The textbook is based on methodological developments, notes by teacher Konstantin Semenovich Shakryl. In the same year, the textbook was submitted for review and was highly appreciated by Academician Simon Nikolayevich Dzhanashia, who was fascinated by the successfully developed and used linguistic terminology. The textbook was published for the first time in 1939 and was reprinted several times over the next forty years, being a reference book for many generations of Abkhaz. Together with the author of the anniversary this year, the textbook “Grammar of the Abkhaz language - phonetics and morphology” celebrates its 60th anniversary,” write Leonid Samanba and Arda Ashuba.

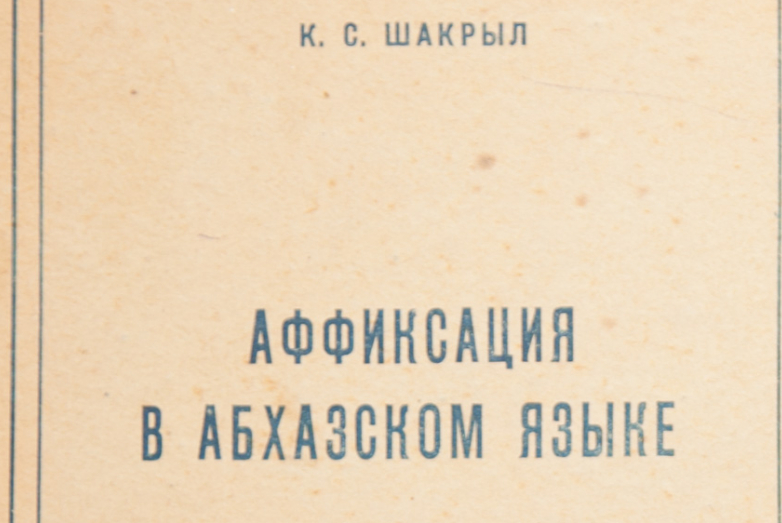

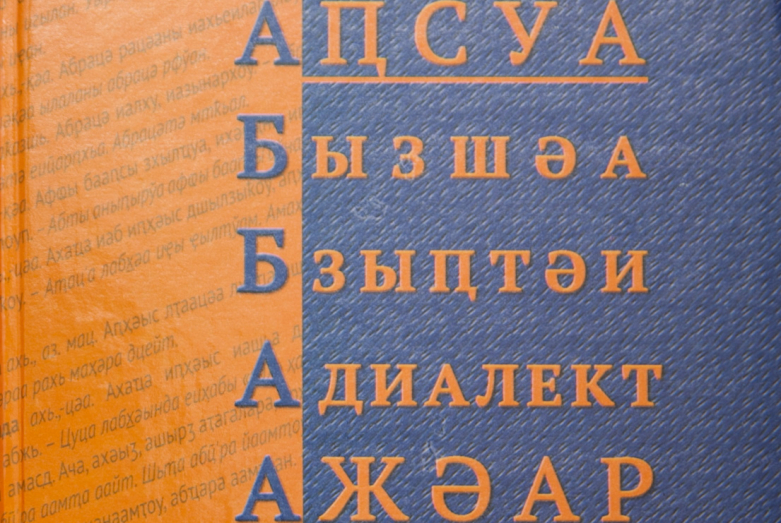

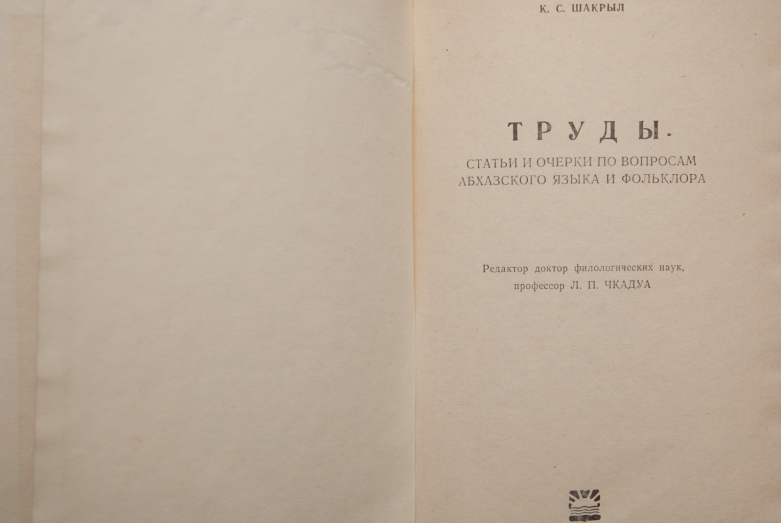

Konstantin Shakryl is the author of more than 100 scientific papers on the issues of phonetics, morphology, syntax, lexicology and dialectology, graphics and spelling, etymology, comparative historical study of the Abkhaz-Adyg languages. “One of the co-authors of the Russian-Abkhaz Dictionary, editor and head of the author’s team of the two-volume Dictionary of the Abkhaz language.” Until the last days of his life, he conducted an active, fruitful research work. Evidence of this is the “Dictionary of the Bzyb dialect of the Abkhaz language”, the “Orthographic Dictionary of the Abkhaz language”, the “Abkhaz-Russian Dictionary”, prepared for publication in 1992, says Arda Ashuba, member of the Supreme Council of the WAC, about the scientific achievements of Konstantin Shakryl.

For great scientific, pedagogical and public services, Shakryl was awarded the Order of the Badge of Honor, medals and diplomas. In March 1961, he was awarded the title of Honored Scholar of the Abkhaz ASSR, in April 1979 - and Honored Scholar of the Georgian SSR. For creating a two-volume explanatory translation dictionary of the Abkhaz language, the scholar was awarded the State Prize of Abkhazia named after Dmitry Gulia. The postage stamp of the Republic of Abkhazia issued in Moscow in 1998 is devoted to Konstantin Shakryl.

Life woven into history

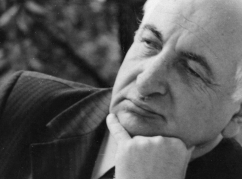

The memory of the innermost moments of life of Konstantin Shakryl, the experiences that he never showed in public, about what a person he was at home at breakfast, how he sang songs in the mornings, what made him angry or happy, and many other personal things are carefully kept today by his granddaughters, Galiya and Esma Kalimovs.

Two terrible tragedies happened in the life of Konstantin. When he was 27, his spouse suddenly died. He never married again. He had two children: the daughter Alexandra and the one-year-old son Boris. Still very young man, it was difficult for him to work, raise children and manage the household at the same time - and they moved to live in the family of the elder brother Platon. But after 11 years, Konstantin was waiting for another blow: his son Boris fell seriously ill. All the efforts of the doctors were in vain, and the 12-year-old boy died.

“It was a terrible tragedy with which grandfather lived all his life,” says the granddaughter of the scholar Galiya.

Despite his pain, Konstantin continued to live and work hard for the benefit of Abkhazia.

Esma and Galiya recall that they spent almost all summer in the Lykhny house with their grandfather.

“In general, we all lived together, as one big family. He was strict. Often, before going to sleep, we loved to “dive” into his room, and then he would tell us fairy tales,” remembers Galiya.

Granddaughters of Shakryl say that the grandfather did school homework with them and generally paid great attention to their upbringing.

“We have always had many guests at home. I remember once I went with my grandfather to the house of Dmitry Gulia. I was very small then. Very famous people came to us, they [with their grandfather] often closed their offices and had long negotiations,” Galiya recalls.

She is sure that it was her grandfather who influenced her worldview, attitude towards her motherland, and language. After all, he himself devoted himself to Abkhazia and its prosperity.

Early in the morning of January 15, 1992, after a little over a month, Konstantin Shakryl died - at the age of 93. Abkhazia bade farewell to one of its distinguished sons. Konstantin Shakryl is buried in the family cemetery in Lykhny.

So the story of the life of one teacher from the village of Lykhny intertwined with a powerful thread into the fabric of the history of an entire people, became a reflection of his national struggle for the preservation of his own culture, traditions and language. Before his death, the teacher and scholar bequeathed his memories to future generations. He wrote a book, which, unfortunately, did not hit the stores, but it’s only copies are kept in private collections of relatives and friends of Konstantin Shakryl.

to login or register.