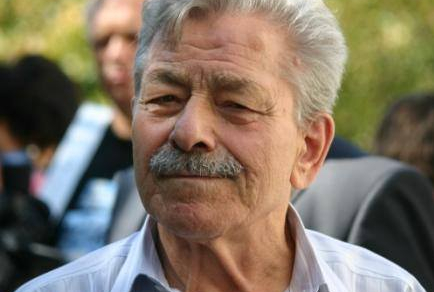

On the birthday of Mikael Chikatuev, the WAC web information portal tells about one of the brightest Abaza poets.

Georgy Chekalov

Mikael Chikatuev was in many ways the first: he was the first from Karachay-Cherkessia to enter the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow and graduated from it; the first of the writers of Circassia published his poem in the “Literary Gazette”; the first of the Abaza authors published his translated books in metropolitan publishing houses; he became the author of the first novel in verses, the first book of vers librers (a form of free verse that is not bound by traditional rhyming principles - ed.), the first book of sonnets in the Abaza language ... He broke into Abaza’s poetry and changed it.

“A song found in the mountains”

Mikael Chikatuev was born on May 3, 1938 in the village of Malo-Abazinsk of Karachay-Cherkessia. When he began to take his first steps, the parents traditionally made a “gylargug” (in Abaza - “gylargvig” - a tradition associated with the first step of a child. Objects are laid out before the kid, and he must come up and choose one of them; it is believed that his profession will be associated with the chosen subject - ed.), and little Mikael picked up a pencil.

According to the recollections of his mother, little Mikael, finding some piece of paper in the yard, grabbed it, ran into the house, put the find on a low chair, in front of which he sat down on his knees and, gently running his finger over the piece of paper, said: “tab tab tab tabzhi”. In a meaningless baby talk, a clear rhythm sounded. Later he will describe this childish “ritual” in one of his poems:

... And I remembered my childhood: in a naive rush

Something from incomprehensible letters folded,

Finger drove on silent sheets:

Tab tab tab tabzhi, tab tab tab tabzhi ...

The future poet went to the Malo-Abaza school for the first two grades. For the rest of his life, he remembered his teacher, Jan Yanovich Sabo, who came every day from the neighboring village by bicycle, and in rainy weather he stayed overnight in a school extension. Mikael loved to come to him there and listen as he read Pushkin's fairy tales by candlelight. It is to Jan Yanovich he will devote these lines:

I'll remember

Good people’s names,

I will be approaching different lights

in the darkness

But in of it

Rural school will be visible:

A man in the window

And the candle on the table ...

Another unforgettable childhood meeting forever etched in Michael's heart was with the Circassian poet Husin Gashokov, who then headed the regional writing organization. It happened in Inzhich-Chukun (administrative center of the Abaza region of the KChR - ed.), where the family moved in 1950. The poet was told about a writing sixth grader, and he came specially from the city to meet him, gave him gifts. Subsequently, Gashokov was always keenly interested in the success of his ward, and he considered it necessary to respond to it in writing, sending him his feedback by mail.

After the sixth grade, Mikael left school to feed the sheep. From the shepherds, who seemed to him to be very old, he heard many tales, legends, and stories that he wrote in his notebooks. From the shepherds, he caught the love of folk songs and sang them, accompanying the sheep to the pasture. And when shepherds from neighboring koshars (pasture - ed.) asked elders about him: “Where did you find this “little song”? - those, smiling, answered: Yes, over there, in the mountains.” Years later, Mikael will call one of his books: “A song found in the mountains,” in which he will say about himself:

I myself felt like a song

Shepherds found in the mountains.

Around the same time, watching the calf, which he drove to a watering place, young Mikael expressed his feelings with verses of his own composition.

“My first poetic lines were in Russian. What is surprising is that after this I have not composed a single poem in Russian for my whole life,” said Mikael Hadzhievich about this case.

“Admit to the Literary Institute without fail!”

A year later, Mikael returns to school and finishes his seven years period of studying, after which he is sent to the regional national boarding school. Once in the city, he often began to visit the editorial board of the Abaza newspaper.

“I will never forget the smile of Kali Dzhegutanov when he met me (one of the classics of Abaza literature - ed.), - recalled Mikael Hadzhievich that period. - He contributed a lot in me. And in 1954, when I was in the tenth grade, my poem was first published in a newspaper. <...> It inspired me so much! So I set foot on this path.”

Three months later, the newspaper posted two poems by Mikael Chikatuev, then another and another.

But, having graduated from the school in 1955, Mikael Chikatuev went to Moscow to enter not the Literary Institute - he did not even know about its existence, but the famous GITIS (State Institute of Theatrical Art - ed.).

“At the boarding school we had a very good drama club, it showed plays in all villages of the region, and I played many leading roles,” explained Mikael Hadzhievich. “And the teachers predicted for me an artistic future.”

He went through two qualifying rounds, but was screened out on the third. As Chikatuev himself said, the reason he was told was his accent.

From Moscow, Mikael traveled to Stavropol that summer and managed to pass documents to the history and philology department of the State Pedagogical Institute, where he entered after passing the exams. Here he joined the group of young poets and together with them attended meetings of the literary association under the regional newspaper “Young Leninist”, which was organized by the graduate of the Literary Institute Vladimir Gneushev. But Mikael studies only one year in Stavropol: probably, with the suggestion of Gneushev, the chairman of the regional organization of the USSR Writers' Union, Valentina Tourenskaya, recommended Mikael to the Literary Institute. In the spring of 1956, he sent his poems there, and in the summer he was summoned to Moscow for an interview.

The institute teacher Alexander Kovalenkov was impressed by the young national poet. “Serious, thoughtful mountaineer; it is immediately visible: a spark of poetry glows in him; he likes the Pushkin’s and Lermontov’s Caucasus. He even read Leo Tolstoy! He spoke interestingly about Hadji Murat. Some good will come out of him,” he wrote in his review.

And the poet Stepan Shchipachev, who reviewed Chikatuev’s poems, turned out to be absolutely categorical, instead of writing a review: “Admit Mikael Chikatuev to the Literary Institute without fail!”

So Mikael Chikatuev was among 116 “lucky ones” selected from 3,000 people after a creative contest, and then among 30 applicants who were admitted to the institute after entrance exams. Very soon, his poem “Love” translated by of Leo Shcheglov appeared in the “Literary Gazette”.

At the institute, students not only studied the history of world literature and culture, mastered the basics of poetic skill. They were regular spectators at the Pushkin Theater, where they passed on student tickets. And on Thursdays they were waiting for a meeting with the great masters of the artistic word.

“The meetings were very interesting,” recalled Mikael Chikatuev. “Even students who, for whatever reason, missed classes on that day, would definitely come to these meetings!” It was interesting to listen to [writers and poets] Sholokhov, Tvardovsky, Ehrenburg, Vsevolod Ivanov, Paustovsky, Boris Chirkov, Semyon Lipkin and many, many others! These conversations - purely creative, frank, very trusting - gave a lot to a student of the Literary Institute, I would say, kindled and awakened in him some kind of special inner light for life! ”

While still a student, Mikael Chikatuev in 1958 released his first poetic collection, “I Take the Aphyharts” (bowed musical instrument, one of the traditional national instruments - ed.). The release of the second collection of “Melodies of Injic” coincided with the graduation from the Institute in 1961. This year was rich for Mikael with happy events: he married, and at the end of the year he had a son.

Bright poetic individuality

Already the first books of Mikael Chikatuev showed that a man with new views on poetry came to Abaza literature. Literary critics point out that in Chikatuev’s works there are features that distinguish them from the rest of the literary products of those years.

“So, the poem “Zalym” (male name Zalim in the Abaza - ed.) is characterized by creative looseness unexpected for the poetry of that time, a free change of rhythms, the successful use of quail sound imitations, and in a contrasting change in the length of the lines of the poem “Raisa”, in a lively, sympathetic intonation, a self-arising rhyming method feels natural, unchallenged structure of Abaza speech,” writes Peter Chekalov, Ph.D. He also considers Chikatuev's poem “Good morning, my village!” as the best work of landscape poetry, and, perhaps, of all the national poetry of the 1950s.

The 60s of the twentieth century, the same researcher calls the turning point for Abaza national poetry, attributing a significant role precisely to Chikatuev in this.

“None of the local poets of that time expressed the expression and energy of the verse as tangible as Mikael, and it is possible to recognize two of his collections as the top ones for the poetry of those years <...>: “Heart Diary” (1967) and “Abaza Horsemen” (1969),” says Chekalov.

It should be noted that in 1964 and 1965 Moscow publishing houses produced two collections of poems by Chikatuev in Russian - not a single Abaza poet has ever been honored so.

One of the important elements of Mikael Chikatuev's innovation was his satirical poetry, which can be characterized by the words of Zinovy Paperny (Soviet and Russian literary critic - ed.): “lyrics brought to fury”.

But this “rage” cost the author considerable nerves. Party functionaries found the verses of the Abaza poet as “undermining the Soviet foundations.” Only the direct intervention of then first secretary of the regional committee of the party, Mikhail Gorbachev (later General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, the first and last President of the USSR - ed.) defused the situation.

Contribution to Abaza and Abkhaz culture

Over the years of creative activity, Mikael Chikatuev has published 14 poetry collections, one book of short stories and legends in the Abaza language, three collections in the Abkhaz and eight collections of poems in Russian. He also published two bilingual collections: “Sonnets” - in the Abaza and Abkhaz languages and “My Abkhazia” (essays, articles and poems) - in the Russian and Abkhaz languages. And in 2011 the Collection of his poetic works in the Abaza language was published in five volumes.

Thus, he became the most published Abaza writer. The poet's handwriting fully justifies the brief and succinct description given to him in the bio-bibliographic directory “Abaza writers”: “A bright poetic individuality”.

For the book of sonnets in the Abaza and Abkhaz languages Mikael Chikatuev in 1998 was awarded the Dmitry Gulia Prize. Earlier, in 1992, he was awarded the title of the national poet of Karachay-Cherkessia and Honored Worker of Culture of the Republic of Abkhazia. This was how his contribution to Abaza and Abkhaz culture was marked.

Mikael Chikatuev maintained close ties with Abkhazia since his time at the Literary Institute, where he became friends with Alexey Gogua and Vladimir Ankvab. Friendship grew into a real creative community. The Abaza poet was filled with love for the brothers on the other side of the Caucasus.

He often traveled to Abkhazia, found his roots there and in recent years, signing his works, he added to the Abaza's spelling of his last name the Abkhaz version - ChkhvotIua. He attached great importance to communication between Abaza and Abkhaz writers, cultural figures and scientists, dreamed that the people divided by the Caucasus Mountains, but united by a common history, language, culture, had a common literature, a common alphabet.

Free poet

Mikael Chikatuev's work activity covers a year of work in the Karachay-Cherkess State Institute, where he was sent by the regional administration after graduating from the Literary Institute, two years in the editorial office of a national newspaper, 18 years as editor in a book publishing house. He worked in the staff of the regional writers' organization, and in a research institute.

But from the end of the 80s he ceased to bind himself with any labor relations and was engaged only in literature, became, speaking with his own words, “a free poet”. One of the possible reasons for this decision was its uncompromising nature. He had his own views on all issues related to Abaza literature: literature and literary criticism, the grammar of the Abaza language, the functions of the national newspaper, and much more. He expressed his opinion categorically, not doubting that he was right, harshly criticizing his opponents. He could not tolerate hypocrisy, he was convinced that only people with a pure soul could create literature.

“I have no middle ground in relations with people: either - or. If a person is close to me, I accept him with all my heart. If he is unpleasant to me, I ruin any relations with him, - the poet confessed. - And even if my friends turned away from me, my relatives were offended - I didn’t move away from the truth and remained faithful to it.”

But far not everyone perceived the truth of Mikael Chikatuev. And at some point, while continuing to write actively, he nevertheless found himself apart from the common literary life.

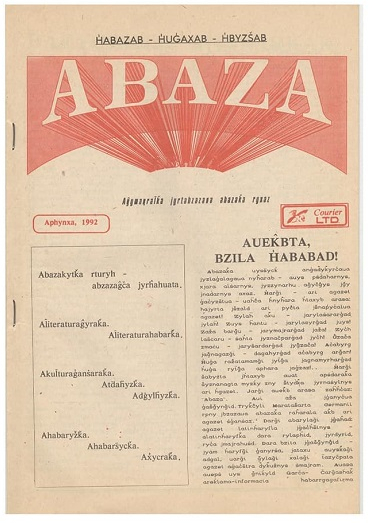

At the same time, Mikael Hadzhievich enthusiastically “clutched” at interesting ideas, took on affairs that could be useful to the people. So, in the beginning of the 90s, he took up the idea of entrepreneur Azamat Tukov to publish a newspaper in the Abaza language for fellow tribesmen living in Turkey in an alphabet specially designed for them. The first and only issue of the newspaper came out in the summer of 1992: the Abaza diaspora in Turkey, to which Mikael Hadzhievich took the print run, took the initiative rather chilly.

In 2007, the “Anthology of Abaza Poetry” was published in two volumes. Mikael Chikatuev was the compiler and the author of an extensive preface to it, in which, not limited to analyzing the state of the national literature, he expressed his point of view on many pressing issues. The publication of the anthology was an event of great importance in the cultural life of the Abaza.

In 2001, Mikael Chikatuev was invited to work as the head of the literary section of the newly formed State Abaza Theater. He edited the plays of other authors, wrote his own, translated works of classics of world drama, and thus did a lot to ensure that pure, lively Abaza speech could be heard from the stage of the Abaza theater.

In one of his poems the poet writes:

I live on earth with a single dream:

To leave after me at least one

Alluring top for the Abaza

Mikael Chikatuev died on March 21, 2014. All his work became the very pinnacle for the people, which he dreamed of.

to login or register.