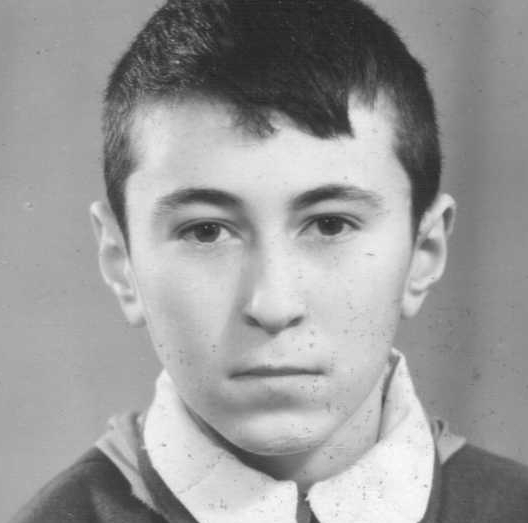

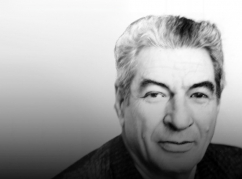

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the birth of the famous Abaza poet Kerim Mkhtse, many of whose works are regarded by literary critics as world heritage. For the anniversary of the poet, the WAC web information portal publishes an essay about him.

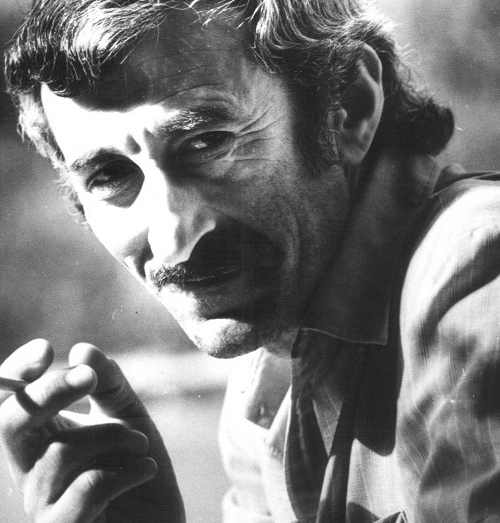

Georgy Chekalov

Literary critics and connoisseurs of Kerim Mkhtse’s poems speak in one voice about the uniqueness of the phenomenon of his work, and the poet Mikael Chikatuev, whom Kerim was introduced to as a child, expressed confidence that even “for a whole millennium” Abaza might not be able to grow another poet like Kerim Mkhtse.” Mkhtse lived a very short life, but left behind him the poetry of tremendous power and beauty.

“For people you gave birth to me ...”

The documents say he was born on May 6, 1949. In fact, Kerim was born the day before. An interesting coincidence: in the Soviet calendar, significant dates of May 5 was celebrated as the Day of printing.

Formally - by father - he was to be called Shavakhov Abdul-Kerim Liuanovich. But his parents separated when he was only three months old, and his father no longer took any part in his life. Enrolling in the first class of the Novo-Kuva primary school, Kerim enrolled in a school magazine surnamed Mkhtse. When he came of age, his passport was issued for the same last name. And he entered the literature as Mkhtse Kerim Leonidovich.

The boy was brought up in the house of Grandmother Kanitat, who, after the death of her husband in battles against the German fascists, alone raised Kerim's mother Alexandra and her seven brothers and sisters. Across the courtyard from her grandmother, her brother Umar Shenkaw lived with his equally large family. Some uncles and aunts of Kerim, both relatives and cousins, were his peers, and he grew up with them, being considered in these families not as a grandson or nephew, but as a son and brother. Because of this, he did not feel fully orphanhood without parents: the mother did not live with him either.

Becoming a poet, Kerim Mkhtse dedicated a lot of aching lines to his mother. He felt guilty before her that the way he was going would not bring him back to her doorstep, and, as if justifying himself, would say:

"What am I supposed to do?

For people you gave birth to me ... "

The poet seemed to feel that he would leave this world before her, and regretted one thing:

"I am afraid that mother will cry bitterly ...

And I beg you - do not offend her."

“More blue” sky over Malaya Kuva

In his native Novo-Kuvinsk, Kerim Mkhtse spent only the first twelve years of his life. In 1961, he was assigned to the regional national boarding school in Cherkessk. From that time on, he was in his small homeland only on short visits. But everything that surrounded him in early childhood remained in his memory forever: countrymen, houses, acacias, a river. And in many of his poems, he chanted his Malaya Kuva - this is the translation of the Abaza name of the village ХъвыжвчкIвын (in the native for the poet Ashkhar dialect - ХъвыжвхвчIы - ed.), wondering how others do not notice that “the sky over Malaya Kuva, though not very much, but bluer and the sun over Malaya Kuva, though slightly, but warmer!”

When did the poet have time to inflame with such love for a village in which he lived so little?

“Probably, this happened when I myself did not realize how much I love Malaya Kuva, - Kerim Mkhtse answered this question. - You feel the real strength of your affection - whether it is towards your homeland or a loved one - when you find yourself away from them. To what extent I love my village, how it entered my destiny, which was formed on this earth, I fully understood only when I left it.”

In the same place, in Novo-Kuvinsk, the first similarity of verses was born, which came out of his pen. It happened when once, when he was still a little boy, he looked at the rain outside the window and suddenly ... he began to cry.

“I then was a third grade student, probably,” Kerim later recalled this episode of his childhood. “Calming down, I took a pen and wrote a few lines.”

Two years later he already could not live without poetry.

Did he then think about the role of poetry in the life of the people and the place of the poet in society?

“What is there!” I did not even understand why I was writing poetry. It was just necessary for me - how to breathe air, take food,” said Kerim Leonidovich.

Uncle Mussa noticed his nephew's passion. He took him to Mikael Chikatuev, who by that time had already graduated from the Literary Institute in Moscow and had time to declare himself in Abaza literature. After some time, several poems by Kerim were first published in the national newspaper “Kommunizm Alashara” (now the newspaper “Abazashta” - ed.), and by the time he finished school he had accumulated about a hundred poems. Written down in four notebooks in an even student's hand, they came to Bemurze Thaytsukhov (one of the classics of the Abaza literature - ed.), who left a written review about them: “They have not yet been combined into a book, but will unite, some of them are not quite mature, but will become mature, the best of them convince that in the future they will become even better. Looking through the notebooks one by one, you feel how the author grows before your eyes.”

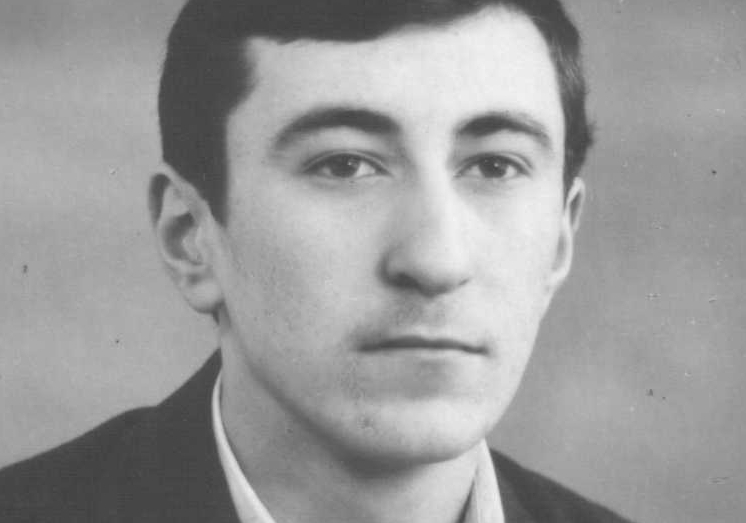

The book of poems by Kerim Mkhtse united when he served in the army: in 1968, his first collection, “My Birch”, was published, a copy of which was sent to him by mail to a military unit.

“His problem is that he became wise early.”

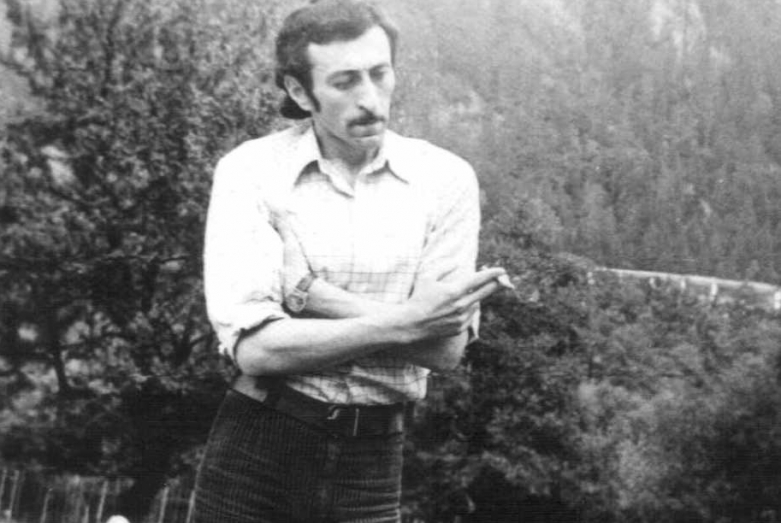

Kerim served in Moscow, where the Literary Institute is located, to which he aspired with all his heart. In February-March 1970, he took his poems there to the creative competition. There were a huge number of people willing to get into the Literary Institute: more than two hundred people applied for one seat! But Kerim passed the competition, was admitted to the entrance exams and successfully passed them.

At the institute, he came to a poetry workshop for the well-known literary critic Alexander Alekseevich Mikhailov, a man of great internal culture.

“He molded me like plasticine,” Mkhtse later admitted.

Already at the end of the first year, the head of the seminar gave his student the following assessment: “He takes poetry seriously. His problem is that he “became wise” early, really wants to appear older than his years, afraid to express himself young, passionate, modern. This is what I call Kerim for. And he has everything else. Confidence in oneself and in themes of modernity can lead him to the high road of poetry.”

The 45 academic disciplines mastered during the years of study at the Literary Institute greatly enriched Kerim's knowledge, broadened his horizons, and helped shape his literary views and worldview as a whole.

Work in the newspaper: publicist, reporter, war correspondent

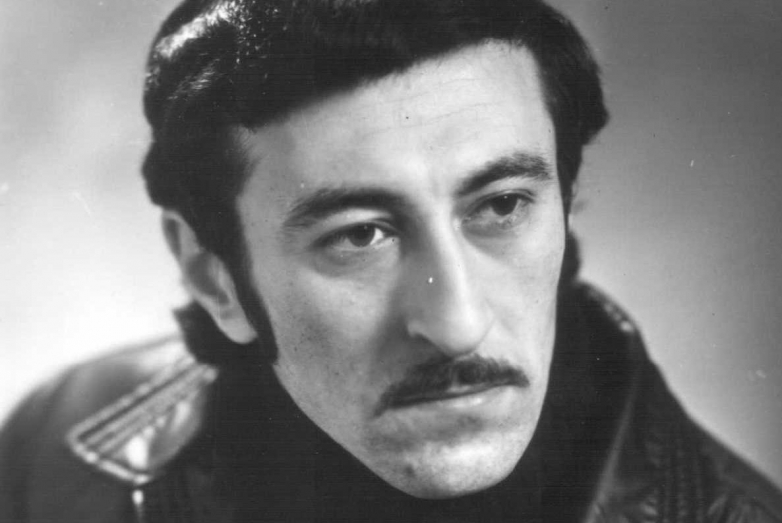

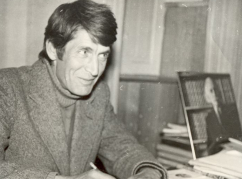

After graduating from the Literary Institute in 1975, Kerim Mkhtse began working in the editorial office of the newspaper “Kommunizm Alashara”. Almost a quarter of a century he gave to the Abaza journalism.

“For me, the editors were not just a place to work, where you perform some functions and get paid. It was for me like a temple for a true believer. I looked at those who worked there like at saints,” Kerim later recalled.

Over the years of work in the newspaper Kerim Mkhtse published a huge variety of materials of different genres and subjects, proving himself as an operational reporter, and as a good expert on literature, and as an excellent essayist, and as a passionate publicist. The best journalistic works of Kerim will later be included in the third volume of his collected works.

In this collection, published after the death of the poet and journalist, the cycle of publications about the Georgian-Abkhaz war stands apart.

When on August 14, 1992 it became known about the invasion of Georgian troops in Abkhazia, Kerim immediately decided for himself that he must be there. But he could not go right away.

While still in Karachay-Cherkessia, on August 27 he published in the newspaper his response to the events in the brotherly republic: “My eyes do not see anything except the flame that has risen above the heavenly land of Abkhazia. My ears hear nothing but shots and tears coming from the mountains and valleys of Abkhazia. In my heart, there is no place for feelings other than pain and despair caused by the Abkhaz tragedy. My mind refuses to think about anything else besides the future of the Abkhaz people fighting for their freedom and the preservation of the ethnos ...”

On September 8, Kerim Mkhtse was seconded to the press center of the government of Abkhazia, temporarily located in Gudauta. Within a month, the reporter sends six articles on events in the Republic to the “Abazashta” editorial office. He was there, where the battles were fought, was next to volunteers from the North Caucasus.

“His presence alone inspired our soldiers for feats,” recalls Zaur Dzugov, chairman of the Union of Abkhaz Volunteers of the KChR.

Returning to Cherkessk, Kerim published ten more materials in the newspaper, which reflected all his feelings from what he saw in Abkhazia.

Later, in 2012 and already posthumously, Kerim Mkhtse will be awarded for his dedicated work on this mission with the Order of the Republic of Abkhazia “Honor and Glory”, and in 2018 - the medal “For Victory”.

Simple like Pushkin

But the main vocation of Kerim Mkhtse has always been and remained poetry. A man of fine nature, endowed with a natural gift and received a solid humanitarian base, he seemed to be thinking and feeling verses. At the same time, he considered his literary work as a service to the people. In the poem “To my people,” he writes:

I will not embellish anything with an elegant syllable.

I firmly know why it is given to me to live:

To glorify in a happy line your joy

To your misfortune compose a requiem.

During his lifetime Mkhtse released eight poetry collections. And, if in the first of them, according to literary critics, there are still weak poems, then the works of the latter are so good that they are comparable with the best examples of world poetry.

This is how Vladimir Tugov, Doctor of Philology, Professor, evaluates Kerim Mkhtse’s poetry: “Mkhtse’s poems are not catchy, they are not dressed in bright poetic clothes. This creates the illusion of artlessness, absolute simplicity. But this simplicity is akin to Pushkin and possesses such a deep philosophical and aesthetic thought that it tries to absorb and express the essence of a multi-complex being. Transparent but inexhaustible depth is probably the most characteristic feature of his poetic individuality.”

Another professor, Peter Chekalov, writes about Kerim: “He is so masterful in his verse form, his mood, and his expressive means of language, that it’s hard to imagine that another poet who will write better than him will appear in Abaza’s poetry”. Peter Chekalov thoroughly researched all the poetic works of Kerim Mkhtze, devoted several articles to him and a whole monograph (“I came here to stay here ...” - ed.) and states with confidence: “Kerim Mkhtse is a bright, large-scale, extraordinary not only within the framework of the Abaza national literature, but in the field of poetry in general without any national or territorial restrictions.”

“In the beginning there was love”

Kerim's poetry is diverse in terms of thematic palette. In the bio-bibliography directory “Abaza writers” the article about him begins with the phrase: “Deep, heartfelt lyric poet.” This brief definition accurately describes the entire poetry of Kerim Leonidovich, especially his love lyrics.

The theme of love in the works of Kerim Mkhtse occupies a large place. Sometimes you are amazed: how can it be so different, and at the same time every time it is so shrill and beautiful to write about love.

At one of the television meetings, Kerim Leonidovich said with a smile: “Probably, those who read my poems think: yes, this guy seems to be dying of love.” And then, in a serious tone, he added that for him love is not only a tender attitude towards a woman, but a much broader concept. This is love for the mother, love for the native land, love for people ... Let's say more: for Kerim Mkhtse, love is the basis of all the foundations, this is what the whole universe is based on.

This idea is most clearly expressed in his short poem “In the beginning there was love”.

How many thousands of years today again

The wise men were not bothered to argue.

Some say: "In the beginning was the Word!"

Others: “No, at the beginning was the Cause!”

Though my path will hardly be easy,

I got to the simple output:

I realized that Love was at the beginning,

That spawned the work and the word.

One of the main and most important themes of Mkhtse’s work is the theme of death and reflections on eternity. The poet refers to it more than once, especially in the last period of his work.

Kerim himself explained it this way: “I am writing about death not because I am afraid of it or in a hurry to die. It is just that every person should remember that he is not forever on this earth. One day he will leave it and go to another world. What will he take with him there, and what memory will he leave here?” The poet believed that everyone should ask himself this question: how he lives will depend on how he answers it.

For the poet himself it was very important to live in harmony with your soul. And he was not so much afraid of physical death, as spiritual.

Dawn, sunset, one after another ...

"The world is not worth the tears of a child ..."

Cruel - the devil carries with him,

And evil will turn into stone ...

Do not be afraid to die, but only

To live forever with a dead soul.

The theme of the fate of the Abaza people passes through all the work of Kerim Mkhtse. It is most vividly reflected in the poem “Abazinia”, written in Russian, and the poem “Remembrance”, where Mkhtse poetic depicted the entire historical path of the Abaza. The poet speaks about the fate of his people with pain, because there were many tragic pages in his history: constant wars, wanderings, when people did not know where they would light up their children’s homes tomorrow. This nation survived and carried through thousands of years its spirituality, its language, preserving them for future generations.

But when in the late 80s - in the 90s of the twentieth century, against the background of political and economic transformations taking place in the country, a reappraisal of values began, people in the pursuit of material goods began to forget about honor, dignity, nobility, about humanity - it was when the pain about the past of the people was replaced in the poet’s mind with anxiety for his future. Having lost their language, their originality, the Abaza will disappear as a people. And Mkhtse ardently tries to explain this to people on the edge of the abyss, to which his people approached.

You Abaza, as if in the world are superfluous,

Slaves, wander, as in a daze.

You are on the edge. But maybe hear

My scream when I fall off the cliff!

Unique texts and their translations

Reading all these poems in a wonderful translation of the Moscow poet Andrey Galamaga, one must bear in mind: for all the merits of the translated texts, they cannot convey the beauty of the Abaza poetry. Truly, the Abaza - one of the most difficult languages of the world - it is worth knowing already only to read Kerim Mkhtse in the original.

And yet, for a poet who wrote in this complex and rare language, the ability to appeal to more people in translation was very important.

In the last years of his life, Kerim Leonidovich himself engaged in translation work - he translated his poems and poems of other Abaza authors from Abaza into Russian. All that he managed to do was included in the second volume of his works. During the life of Kerim Mkhtse, not a single translated collection of his poems was published, only a few poems were translated.

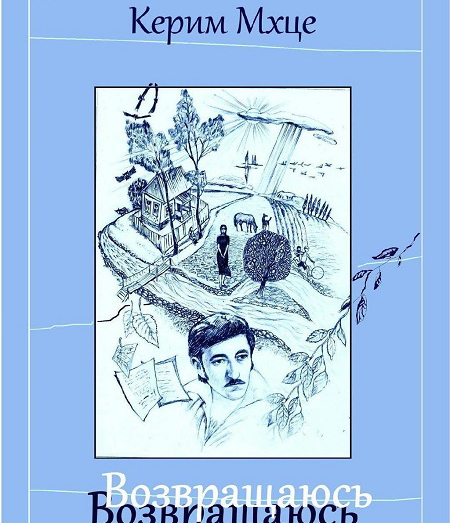

In 2013-2018, the International Association for the Development of the Abaza-Abkhaz ethnos “Alashara” implemented a translation project initiated by Peter Chekalov. Its result was the collection of poems by Kerim Mkhtse “I Return” in Russian (as translated by Andrey Galamaga). According to the author of the project, the collection allows the Russian-speaking reader to gain some insight into the creative appearance of the Abaza poet, break the narrow national circle of fame and bring Mkhtse's poetry into the all-Russian literary orbit.

“Something that cannot be learned”

According to the well-known thought of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, genius is “the ability to create something that cannot be learned.” Trying on this statement in case of Kerim Mkhtse, Professor Peter Chekalov writes that in many works of the poet - the poem “Remembrance”, the cycles “Diary Pages”, “The Bright Island of Pain”, numerous poems - expressed what really “cannot be learned in any Literary Institute, to gain any practical skills.”

“Such works can only be called an inspirational impulse, a breakthrough, - the researcher of Mkhtse is sure. - We cannot reasonably and logically explain what this sensation of the highest harmony, charm, and the strongest aesthetic effect, similar to spiritual shock, derives from. <...> Here merged together rational and irrational, inaccessible to the mind, ineffable in any logical concepts and judgments, built on artistic sense and intuition. Such works convince: it is impossible to learn what Kerim possessed. This is the highest gift, not amenable to any algebraic calculus.”

Be yourself - the privilege of the great

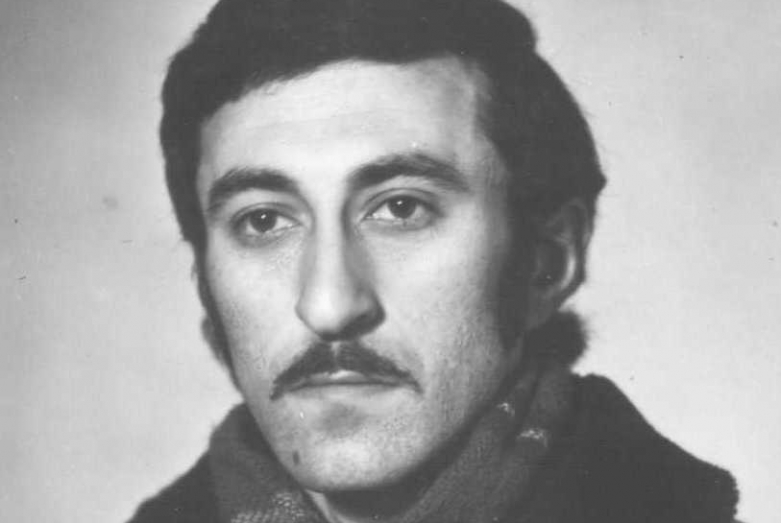

Creativity of Kerim Mkhtse was noted at the official level. In 1998, he was awarded the honorary title “People's Poet of the Karachay-Cherkess Republic”, in 1999 he won the Umar Aliyev Prize for his contribution to the development of Abaza literature.

But Kerim Leonidovich himself was rather skeptical of all kinds of formal honors, believing that the most important thing was the recognition of people.

The creative evening of Kerim Mkhtse, held on March 17, 2001, was a testament to the tremendous love of the poet. It took place in the full-fledged hall of the Republican Drama Theater in Cherkessk and turned into a great celebration of poetry. People managed to say good words to the poet during his lifetime.

Less than a month after this meeting - April 12 - he was gone.

Not everyone manages to be himself in life. Kerim Mkhtse succeeded. It is his greatness that was noted by the Karachai poet Yusuf Sozarukov, who responded to the death of his brother in the pen with the quatrain-dedication “King”:

When the king and the joker change places

And elsewhere evil rules,

Then the king is the one who is in a world shame

Dares to be himself, sending the whole world to the jokers.

In one of the last TV programs with the participation of Kerim Mkhtse, the poet himself, assessing the past years, said without any slyness that he was happy with his life, but not happy with himself, because “he did very little of what he wanted and could have done.” He did not regret that he did not hold high ranks and did not accumulate wealth. For him it was much more important that he lived his life as a person. And he was proud that “he remained the same as in his youth.”

to login or register.